It’s hard to underestimate the achievements and long-lasting contributions of our third U.S. president. Thomas Jefferson was a founding father of our nation, author of the Declaration of Independence, diplomat, political philosopher, architect, horticulturist, and inventor. He also founded and designed the University of Virginia, negotiated the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France, and launched Lewis and Clark on their expedition to the American west.

The very existence of Gateway Arch National Park (formerly Jefferson National Expansion Memorial) is a testament to Jefferson’s vision of a nation that would span the continent.

Yet despite Jefferson’s accomplishments, many scholars continue to find him an enigma, especially when it comes to slavery. Though he referred to the institution as an “abominable crime” and a “hideous blot,” he enslaved more than 600 people over the course of his life and kept an enslaved young girl as a concubine. How can we reconcile this paradox?

First, we should acknowledge the life of the young Jefferson: his upbringing was one of wealth and privilege. His father’s enormous plantation in colonial Virginia was supported by the work of at least 60 enslaved laborers who toiled in the gardens and fields, tended the livestock, and worked in the family home. As a young man, Thomas inherited lands from both his father and his father-in-law, eventually administering a sprawling 5,000-acre plantation planted mostly in tobacco. Like other wealthy landowners in the South, he could not have managed Monticello without the contributions of the enslaved men, women, and children he also inherited.

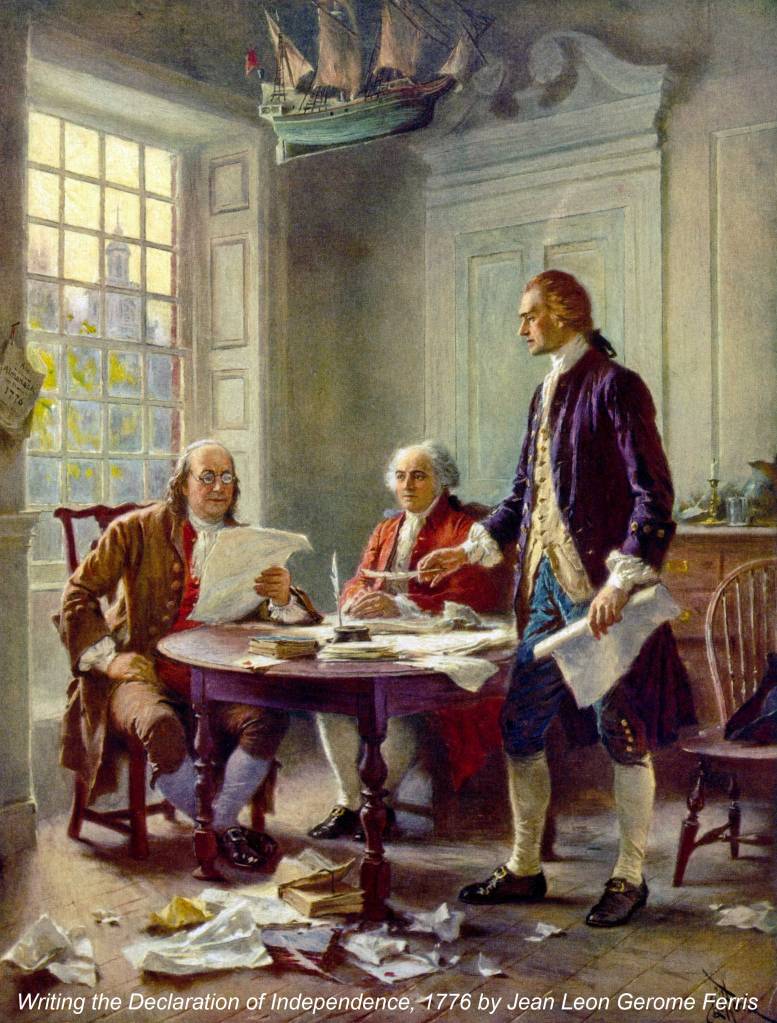

Yet over time, Jefferson began to see slavery as a “moral depravity.” In fact, as he was writing the Declaration of Independence in 1776, he included a 168-word anti-slavery clause that blamed King George III for his role in creating and perpetuating the slave trade. Some of the accusations he made:

The entire anti-slavery clause was later deleted from the Declaration by delegates to Second Continental Congress, one-third of whom were enslavers. Decades later, Jefferson attributed the removal of the controversial text to the wishes of delegates from South Carolina and Georgia, who strenuously objected to any ban on the importation of slaves. The founding fathers who had opposed slavery – including Jefferson – did not insist on retaining the clause, fearful of dividing the fragile new nation.

In recent years, Jefferson scholars have delved more deeply into the lives of the enslaved people who lived at Monticello. Among them were the many generations of the Hemings family, who held important jobs in the household. Young 14-year-old Sally Hemings is thought to have been the daughter of Jefferson’s father-in-law, John Wayles.

It was with this enslaved girl that Jefferson carried on a life-long affair, and with whom he fathered several children. DNA evidence has shown that Jefferson fathered at least one of Sally Hemings’ sons, bearing out the truth of the old rumors and political slander that accompanied this liaison. Jefferson cared for Sally’s biracial children and eventually freed them. However, Sally Hemings was never legally emancipated. Instead, she was unofficially freed—or “given her time”—by Jefferson’s daughter Martha after his death.

Clearly, Thomas Jefferson’s relationship with slavery was a painful and complicated one. Yet he will always remain an important founding father and influential force in the formation of our nation.