You don’t have to be a birdwatcher to appreciate the need for preserving our feathered friends. Beyond their beauty and fascinating behaviors, birds are critical components of nearly every ecosystem on Earth. They play many roles – as predators, prey, scavengers, seed dispersers, and pollinators. They also respond quickly to changes in their surroundings, making them good indicators of environmental conditions. Monitoring bird population numbers is an important way for biologists to assess the health of local habitats.

The National Park Service regularly monitors birds at many of its parks, both to study the wellbeing of its sites and to monitor the effects of climate change and other human-caused disruptions. These efforts provide crucial conservation data, helping park managers improve the health and function of their sites’ habitats.

NPS biologists have been monitoring songbird populations at Voyageurs National Park in northern Minnesota since 1995, conducting annual songbird surveys each June at 60 different points across the vast park. More than 100 species of songbirds have been documented there.

The six most common were the ovenbird, red-eyed vireo, Nashville warbler, white-throated sparrow, and blue jay, in that order. Many birds, such as the white-throated sparrow and the Canada jay, find their way to the park from conifer forests extending all the way to the Arctic.

But the bird surveys at Voyageurs are showing mixed results. The white-throated sparrow has shown a 49% decline in observations since 2019, followed by a 22% decline in ovenbird observations.

In fact, the total number of individuals of all species recorded in Voyageurs is down 21% from 2020 to 2025. Species richness, or the number of species recorded, is down 7% over the same period. Some of this can be explained by missing some survey locations due to inclement weather, and limited time and/or personnel to conduct the surveys.

On a more positive note, the black-throated blue warbler, blue-headed vireo, and wood thrush are showing the highest increases in observations over the last five years, all of them over 200%. Biologists are still assessing the reasons behind these fluctuations.

Researchers also predict a good news/bad news scenario in the future. One NPS study analyzing two different climate scenarios predicted a high turnover of species in the park by mid-century (2041–2070) if the nation continues on its current path of rising greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, two of the most common species at Voyageurs today – the red-breasted nuthatch and the white-throated sparrow – are predicted to disappear from the park by mid-century, while the nuthatch may only appear during the winter months.

Meanwhile, the populations of birds more commonly found in open country and residential areas such as the blue jay, American goldfinch, Baltimore oriole, and common grackle are predicted to improve, and additional species are expected to move in.

The situation for bird life is comparable at Mississippi National River & Recreation Area in Minnesota. NPS researchers there annually conduct songbird surveys at 49 locations scattered among nine city, county, and regional parks in the 72-mile length of the national park boundary. A total of 88 species has been documented, (an average of 62 species per year) since the studies began in 2015.

The black-capped chickadee was the most densely populated species in the park followed by American goldfinch and American robin (84 birds/mi2). Populations of the Eastern wood-pewee are also on the rise.

But scientists are tracking the small declines in insect-eating birds like warblers and flycatchers, as well as other species. They are also concerned that the effects of climate change may cause a decrease in the numbers of goldfinches and robins in the summer, though they’re predicted to fare better in the winter.

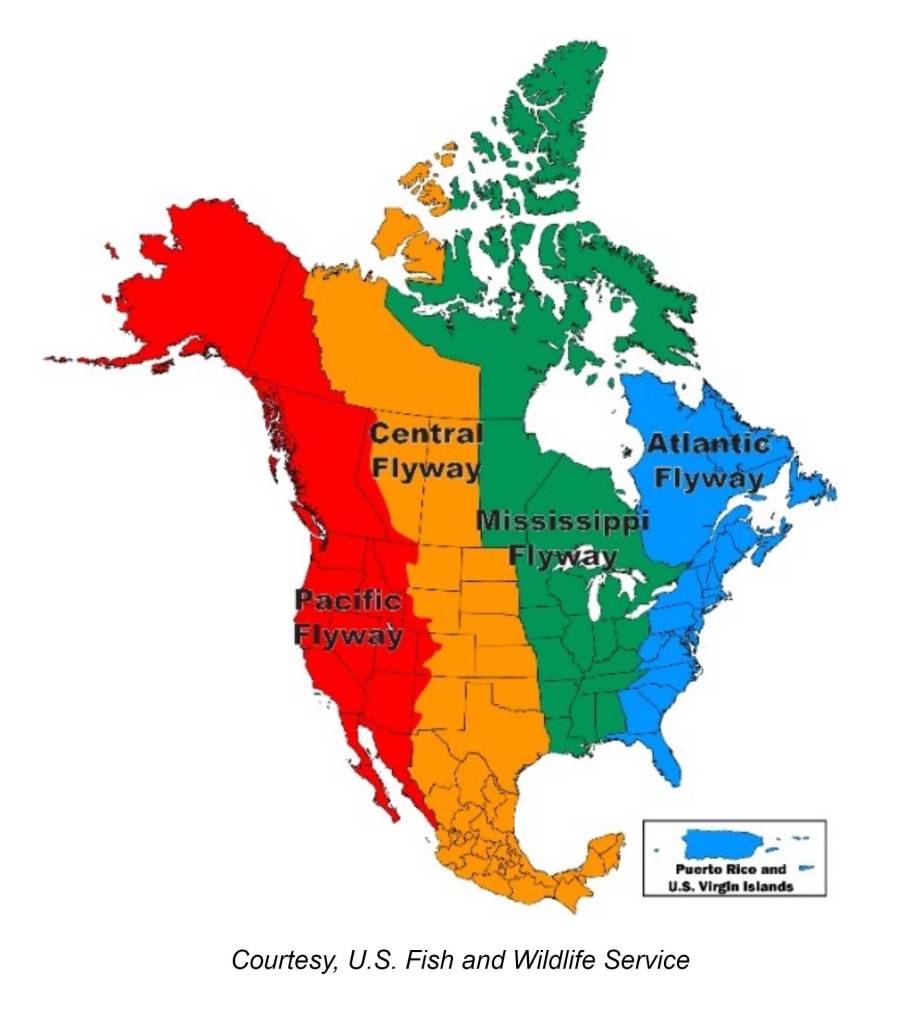

This Twin Cities park and its surrounding areas benefit from their position along the Mississippi River, one of North America’s four major flyways for migrating birds. An estimated 325 bird species use this route twice a year, flying between their breeding grounds in Canada and the northern U.S. and their wintering grounds along the Gulf of Mexico and in Central and South America.

The rich diversity of habitats along the Mississippi River valley are a haven for many birds who stay for the summer to nest and raise young. It is little wonder that this large, south-flowing river forms the core of one of North America’s great flyways and offers birders wonderful opportunities to observe a wide variety of species.

It’s doubtful that a day will come when songbirds are completely absent from our national parks. They will continue to enchant us with their song, though some of the future performers may be new.

If you’re interested in identifying birds that you see in the wild, or just in your own backyard, the National Park Service can help. Check out this simple identification key that can help you recognize just who you’ve spotted, and will link you to more information about your feathered friends.