A difficult chapter in the history of race relations in America is the focus of one of JNPA’s newest park partners. Springfield 1908 Race Riot National Monument was included as a National Park Service site in 2024. It commemorates the events of August 1908, when African American residents of Springfield, Illinois, were targeted and attacked by thousands of White residents.

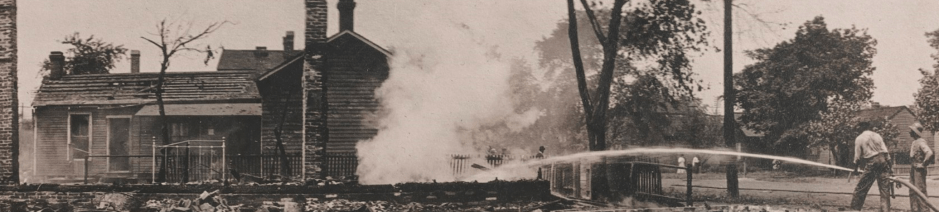

The riot erupted after two Black men were accused of crimes (many of them later unsubstantiated) against White residents. As with many other race riots of this era, the accusations served as a pretext to force Black residents from their communities. White mobs in Springfield destroyed Black homes and businesses and lynched two Black men. After three days of violence, the state militia helped restore order, arresting approximately 150 participants. Few, however, were ever convicted.

This shameful episode was just one of numerous incidents of racially motivated riots and violent acts that took place in many American cities in the late 19th and early 20th-centuries. This particular riot captured national attention because it took place in Abraham Lincoln’s hometown. It eventually led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909.

The National Monument was established in August 2024 very near where the 1908 riot started. While there is nothing left of the original buildings, archeological evidence gives a rare glimpse into a community devastated by racial hatred. The foundations of five homes and related artifacts show how residents lived in the predominately Black neighborhood called the “Badlands.” The site is a rare surviving resource directly associated with race riots in America.

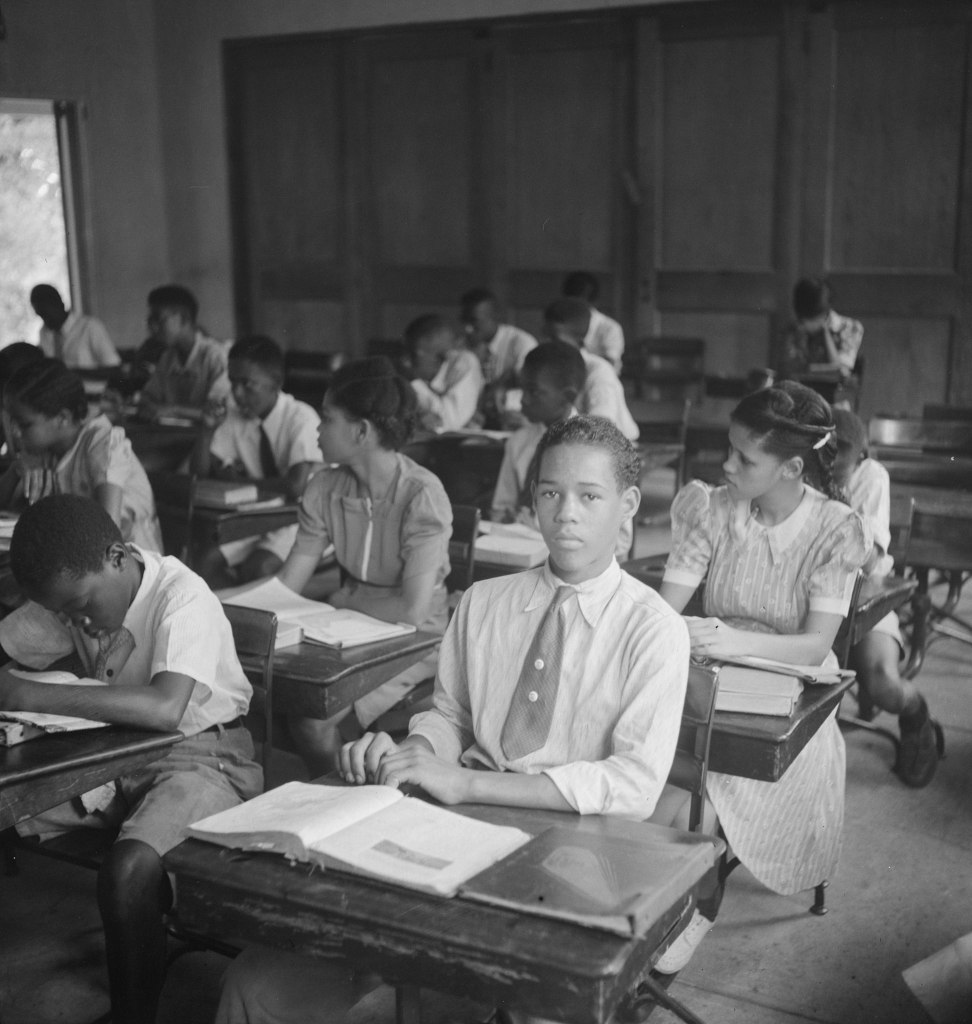

Those interested in visiting the Springfield Race Riot site can begin their journey at Lincoln Home National Historic Site, just one mile away. There they can get information about the new National Monument and discover a self-guided walking tour of the park. Eventually, the National Park Service plans to develop programs and facilities to breathe new life into the stories surrounding the Springfield race riot. This is part of the agency’s ongoing commitment to telling a more complete story of the civil rights movement in America. JNPA is proud to be a partner in this endeavor.