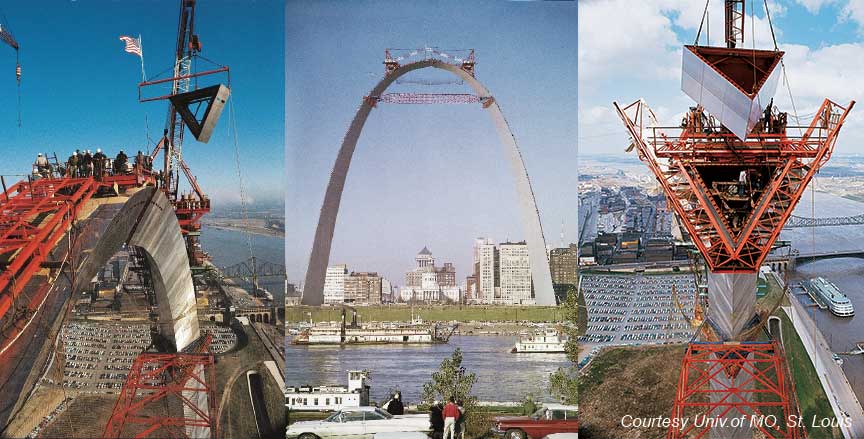

The Gateway Arch is celebrating its 60th anniversary and you’re invited to be part of the celebration! Sixty years ago on October 28, 1965, the final keystone piece was laid at the top of the monument, joining the two curving stainless steel legs of the 630-foot structure. Once that important triangular piece was inserted, the Arch soared into history as a symbol of Thomas Jefferson’s vision of westward expansion. And it took its place as the tallest manmade monument in the U.S.

To commemorate this historic event, starting tomorrow Gateway Arch National Park will host three days of fun – and free! – crafts, musical performances, and activities. (The park has temporarily reopened until November 2 despite the government shutdown.)

Highlights include:

- Visits from some of the Arch builders, men who helped construct the Arch 60 years ago, who will autograph posters for visitors and reminisce about their contributions to the building of the monument

- A fireworks display under the Arch

- A performance by the Marching Eagles band from Columbia (IL) High School

- Performances by the St. Louis Arches, the high-flying acrobats from Circus Harmony

- Children’s craft activities, including building the “Arch” with giant blocks, getting a (washable) Arch tattoo, posing as an Arch builder or park ranger, and signing a giant birthday card.

- A visit by St. Louis Cardinals mascot Fredbird, as well as other local team mascots.

And for the lucky ones who purchase a ticket on the Tram Ride to the Top on October 28, you’ll become an exclusive member of the Tram Ride to the Top Club, entitling you to a special certificate. We highly recommend purchasing your tickets in advance as they are expected to sell out.

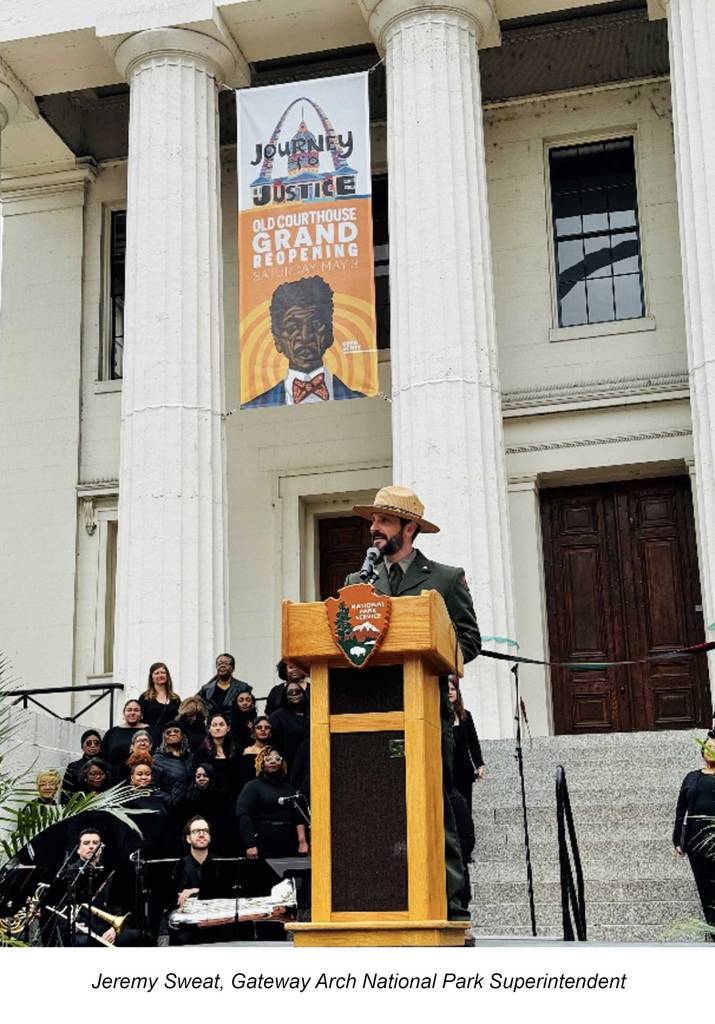

It’s not often we get to commemorate a milestone anniversary of the completion of one of the world’s most iconic monuments. JNPA is proud to have led the collaborative private effort to temporarily reopen Gateway Arch National Park even in the face of the current government shutdown, enabling this birthday celebration to take place. We hope visitors take this opportunity to visit the Arch and Old Courthouse while it remains open through November 2.

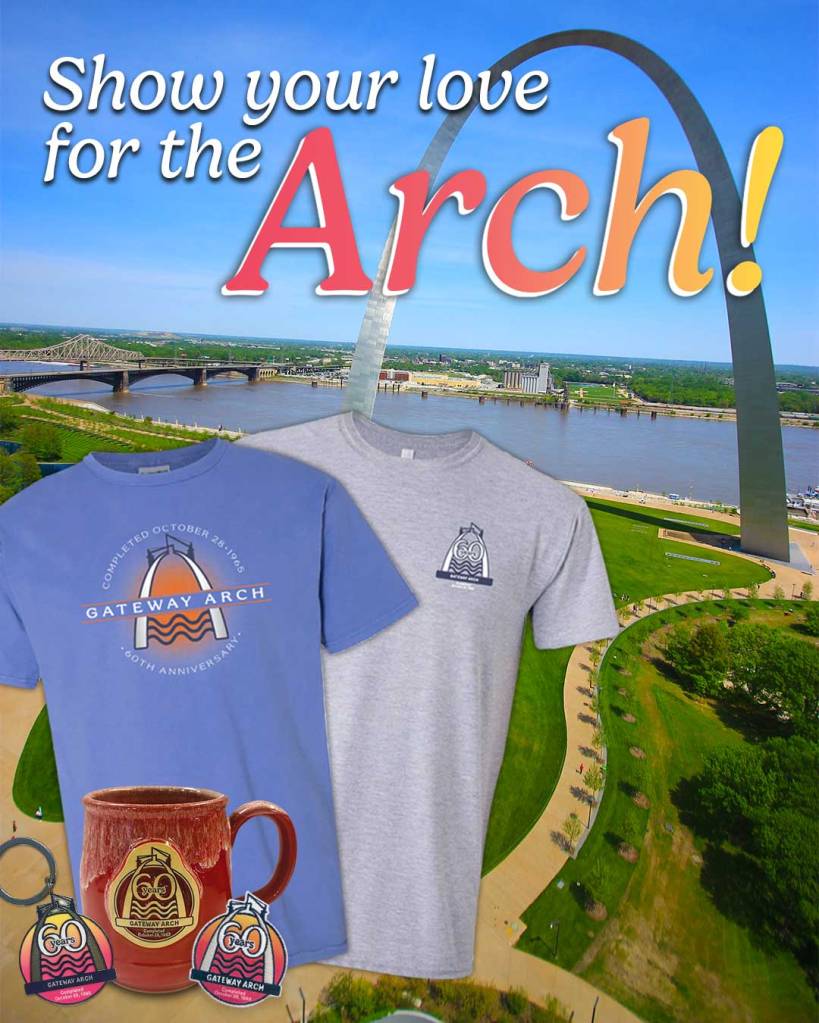

If you can’t stop by for a visit, you can still honor the Arch anniversary with one of our commemorative 60th anniversary products, available from our online store. Show your love for the Arch and help support your favorite park!