National parks aren’t just for adults. If you’re planning a trip to a park with your kids this summer, make sure you check out the site’s Junior Ranger activities when you visit. These programs help children appreciate and connect to our parks – whether it’s walking in the footsteps of famous people, exploring beautiful landscapes, developing new interests, or just having fun.

Here’s how it works: Before your visit, go to the park’s webpage to learn about its special kids’ activities. Most of the nation’s 400+ national park sites offer Junior Ranger programs. When you’re on site, check in at the visitor center. That’s where kids will typically receive a free park-specific activity book that helps them learn about the landmarks, history, wildlife, geology or other themes unique to that park.

After your kids complete the activities in the book, they’ll need to present it to a park ranger to receive a special Junior Ranger badge and certificate. Often, they’ll also take a pledge to learn, protect, and explore their national parks.

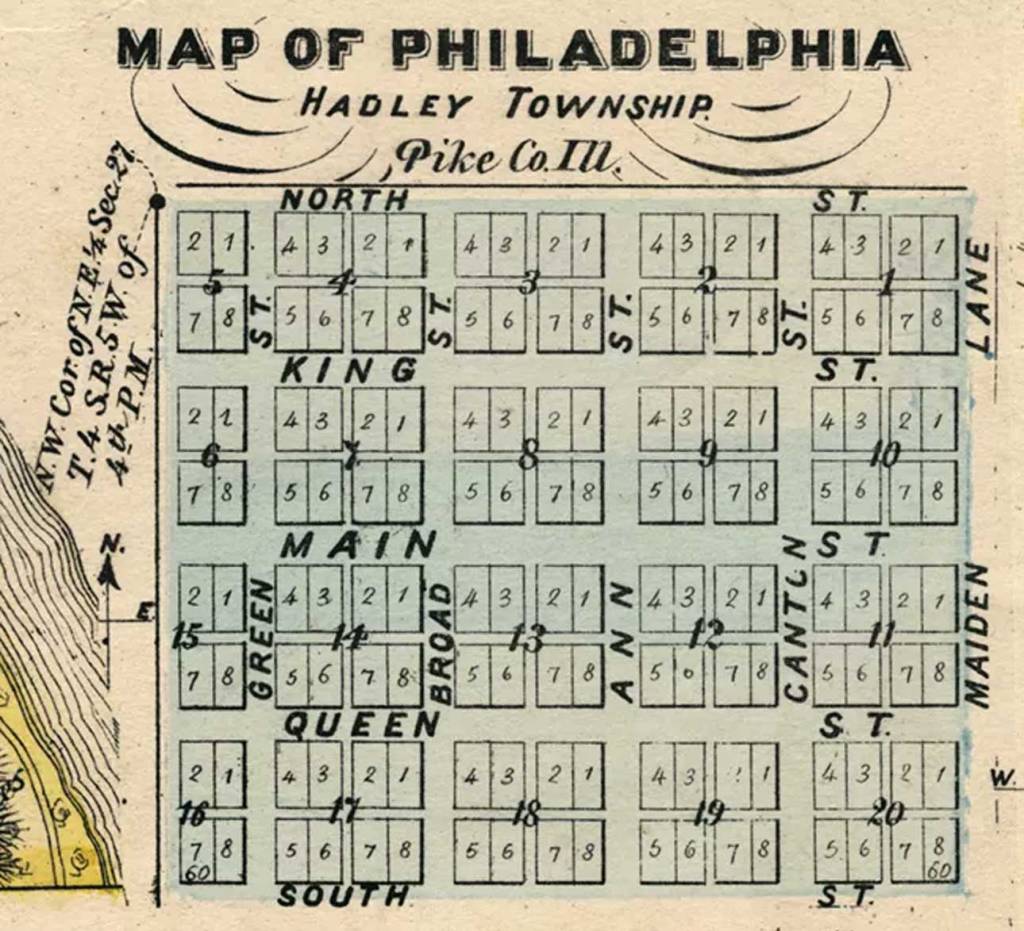

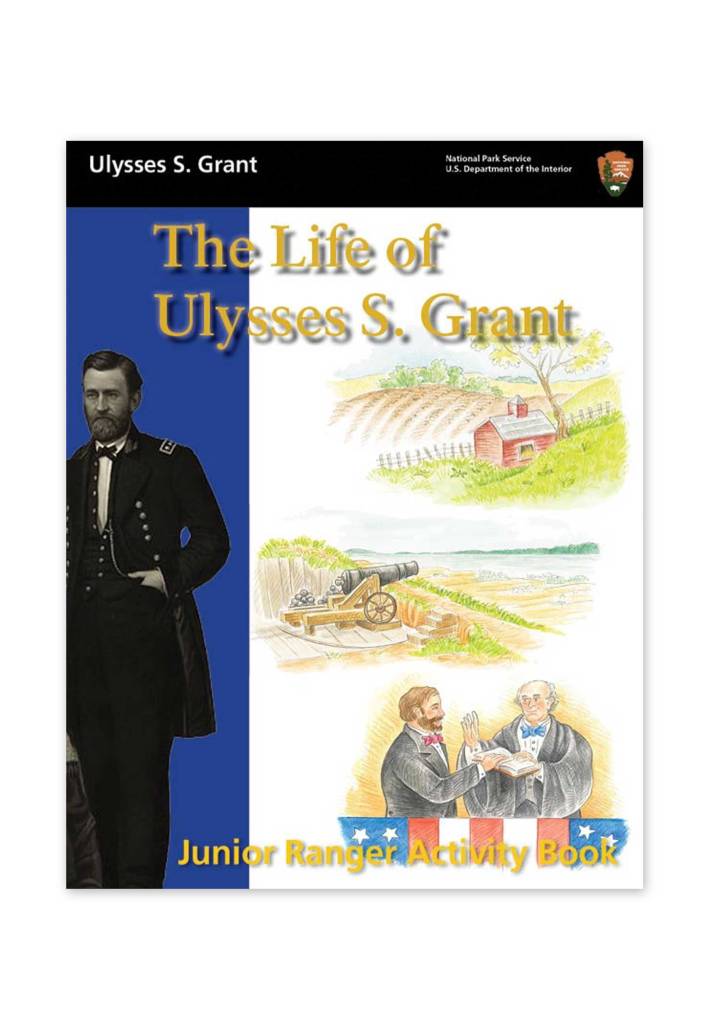

For kids who can’t visit in person, the National Park Service website offers a Junior Ranger Online section featuring videos, games, and songs, allowing families at home to connect with parks around the country. And many parks have their own Virtual Junior Ranger programs. Voyageurs National Park, for instance, includes fun activities on its website, as well as the opportunity to download the Virtual Ranger badge. U.S. Grant National Historic Site created a special Bicentennial Virtual Ranger Activity Book to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Grant’s birth.

Finally, for those kids who want to go the extra mile, why not let them dress like a park ranger with a special Junior Ranger Vest and Flat Hat! JNPA carries a wide range of Junior Ranger products like these in our online store, including mini building blocks, pins, and activity books.

However you introduce national parks to your kids, they’ll be sure to get more out of their visits when they become Junior Rangers!