November is Native American Heritage Month, an opportunity to celebrate the traditions, histories, and cultures of Indigenous American communities across the country. What a fitting time to honor the original inhabitants of what is now Voyageurs National Park.

People have occupied the lands in northern Minnesota as far back as 10,000 years ago. Small family groups of Paleo-Indians entered the region as the waters of the vast glacial Lake Agassiz receded. These were nomadic hunter-gatherers who made use of the abundant resources the lakes and forests provided. They followed the migrating game, fished the rivers and lakes, and collected edible and medicinal plants.

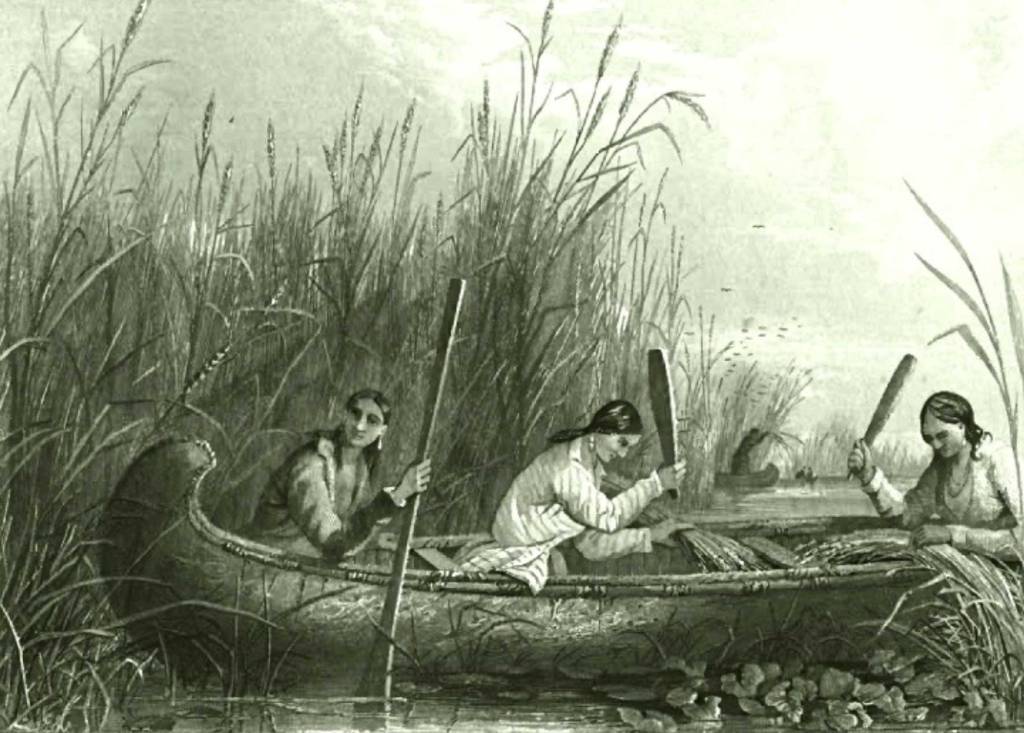

As time went on, the Native Americans increased their reliance on local wild rice, which once grew in abundance along the lake shores. They particularly valued this nutritious food source because it could be stored for later use during the difficult winters. Because the people didn’t have to travel so often in search of game, they could adopt a somewhat more sedentary lifestyle.

It was during this so-called Woodland Period (100 CE to 900 CE) that the Indigenous populations began using ceramic materials to create arrowheads and projectile weapon points. Samples of these tools have been found at hundreds of archeological sites within the park’s boundaries, giving researchers a window into the lives of these long-gone people.

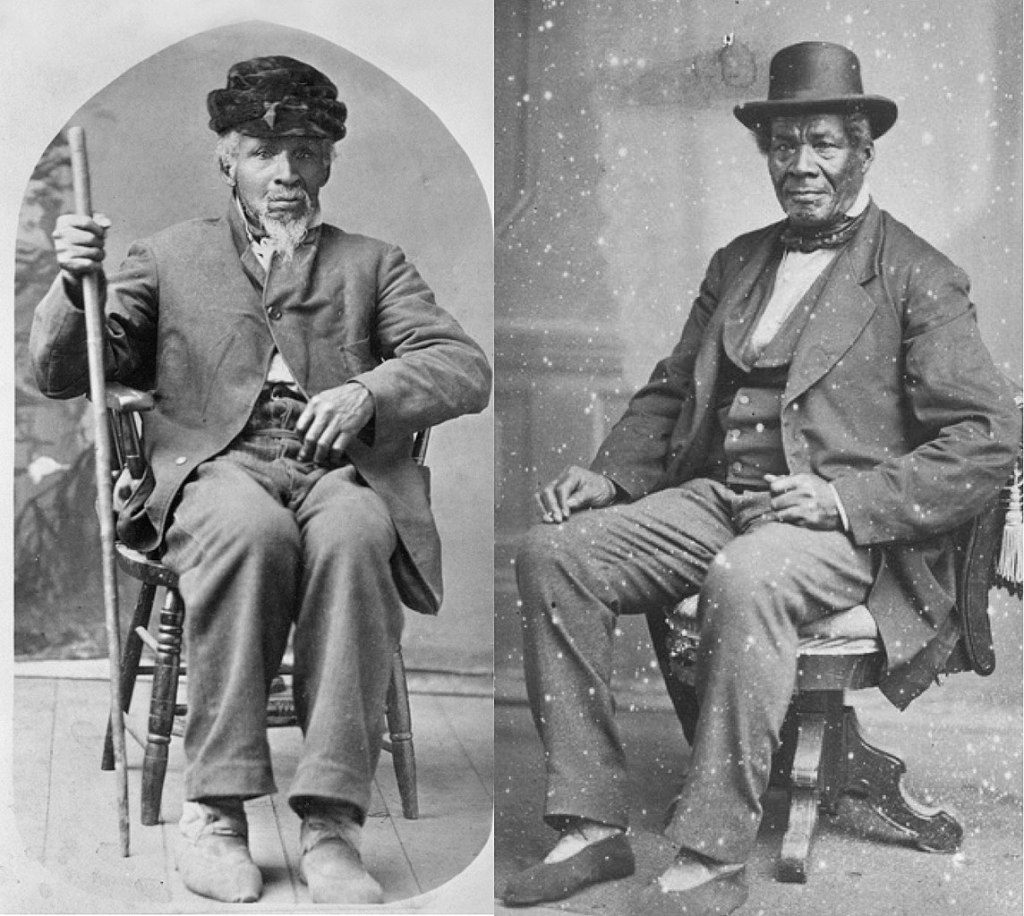

When Europeans first arrived in the Midwest in the mid-1600s, they encountered several different Indigenous groups living in Minnesota. European settlements on the East Coast had forced some tribes west, including the Chippewa (also called the Ojibwe), the primary American Indian group who wound up occupying present-day Voyageurs National Park. National Park Service archeologists have pieced together the daily lives of the Bois Forte people, the main Chippewa group, who left evidence of their lives from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Ojibwe willingly traded with the newly arrived Europeans, both with the settlers and with the French-Canadian “voyageurs” who navigated the area’s waterways in the 1700s and 1800s for the fur trade (and for whom the national park is named). The tribes supplied the newcomers with furs and with vital supplies like food, fish, and canoes.

There was also a significant cultural exchange between the two groups. Many Europeans adopted Native American diets as well as some aspects of their semi-nomadic lifestyle, while both groups sometimes celebrated holidays together.

By the mid-1800s, the Bois Forte Chippewa numbered about 600 to 1,000 people. But contact with Europeans ultimately brought sweeping changes to their society, as the white settlers introduced new lifestyles, ideas, technologies, and even deadly diseases. Treaties in 1854 and 1866 ultimately stripped the Bois Forte of two million acres of their homeland, which was coveted by timber companies. Dams built to facilitate logging had destroyed the vast wild rice beds of the local watershed.

Gradually, the local Ojibwe moved to the Nett Lake reservation. By the 1930s, only a few scattered groups of Bois Forte people lived in the park permanently, though larger numbers returned seasonally for blueberry picking and other harvesting. Despite the decimation of their society, the tribe never warred with the white settlers

Today, it’s hard to find evidence of the Bois Forte Chippewa within Voyageurs National Park; only a few locations bear names that reference the tribe’s presence. And yet, a number of modern Native American nations continue to have connections to the area. The park staff is collaborating with a variety of Tribal governments to better involve them in the stewardship of the park. This past summer, the NPS and the Voyageurs Conservancy hosted a series of workshops to help integrate Tribal knowledge into park management, stewardship, interpretation, and education.