Pop quiz! What animals are small, furry, eat thousands of mosquitoes every night, and are critical to many natural ecosystems? Bats!

National parks are home to 45 species of these cute (to some!) little mammals, each of which play an important role in nature. Yet they have recently been decimated by a deadly disease. Luckily, Missouri National Recreational River and many other national parks are working to rescue bat populations.

Why is it so important to protect bats? In contrast to the pop culture depiction of tiny flying vampires, most bats eat insects, fruit, plant nectar, or small animals such as fish or frogs. In fact, only three of the nearly 1,500 bat species in the world drink blood, and they only live in Central and South America. Insect-eating bats feed on so many flying pests that their contributions would add up to more than $3 billion worth of pest control in the United States alone!

Additionally, bats are excellent pollinators. Do you enjoy tequila? Well, thank bats because they are the number one pollinator of blue agave! Bats also contribute to the ecosystem by supporting cave communities, distributing seeds from the fruit they eat, and serving as prey to other animals. Bats have even inspired technological advances such as sonar systems designed after bats’ echolocation and new types of drones inspired by bats’ thin, flexible wings!

It’s clear that bats are AMAZING animals, so what is wreaking so much havoc on their populations? It’s a disease known as white-nose syndrome, caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans. The fungus infects bats during hibernation, covering their face and wings. This causes the bats to wake up more frequently, use up their fat reserves, and starve before winter is over. The fungus is easily transmitted through physical contact, either with infected bats or on cave surfaces. Because the fungus spreads through contact, it can also be carried on shoes, clothing, and supplies. That’s why scientists urge people who visit caves to thoroughly decontaminate all of their clothing, shoes, and supplies before and after their visit.

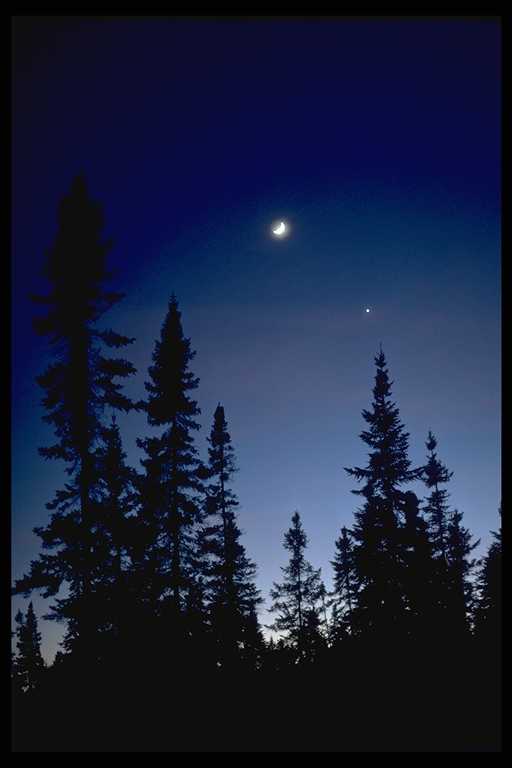

Missouri National Recreational River, a JNPA partner park, began an acoustic monitoring program in 2014 to monitor bat populations in and around the park. Acoustic recorders were installed to detect the calls bats use for echolocation. Different species of bats have different calls, so this system can also determine what species are in and around the park. Researchers then review the recordings and analyze the data.

So far, scientists have determined that eight species of bat call the park home: the big brown bat, eastern red bat, hoary bat, silver-haired bat, little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, evening bat, and tri-colored bat. Although white-nose syndrome has been detected in nearby populations in South Dakota, thankfully it has not been detected within the park boundaries.

If you want to learn more about bats and how to help protect them and their habitats, visit the National Park Service website.