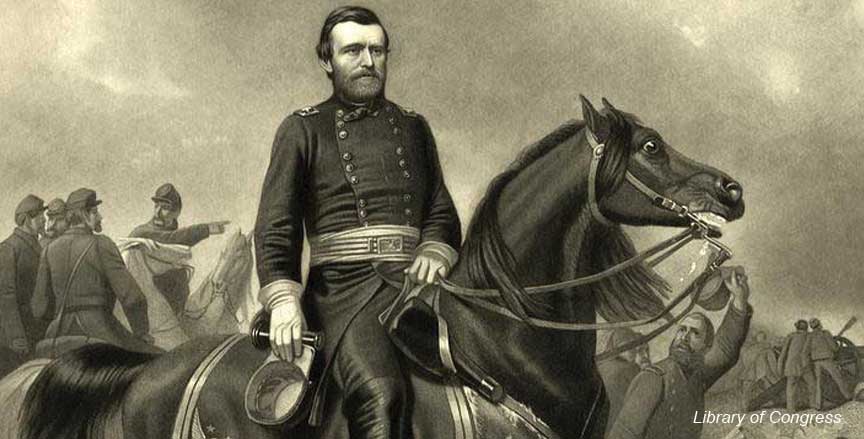

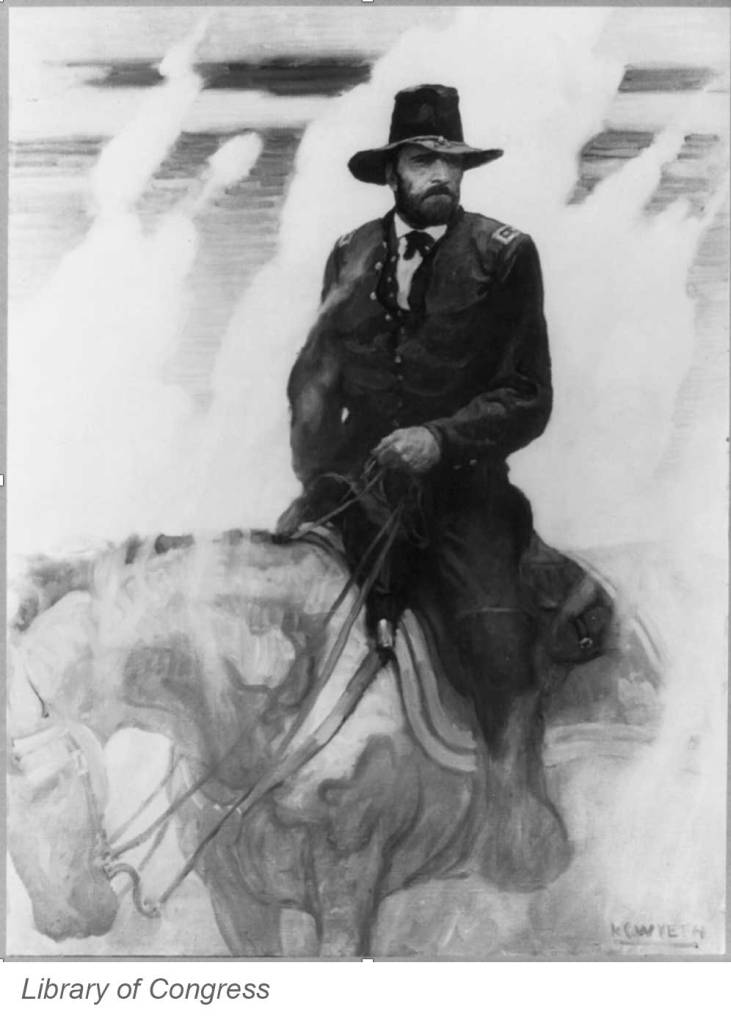

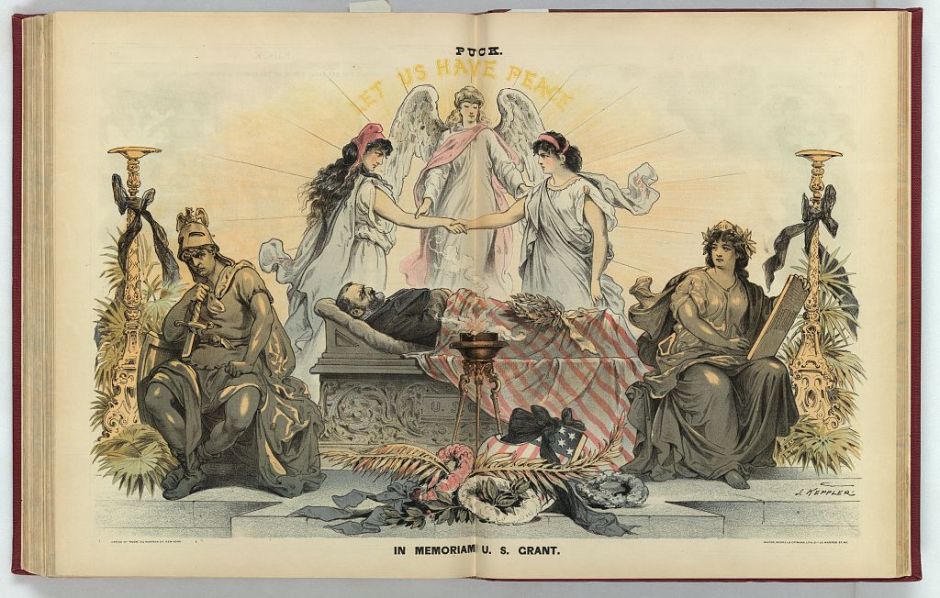

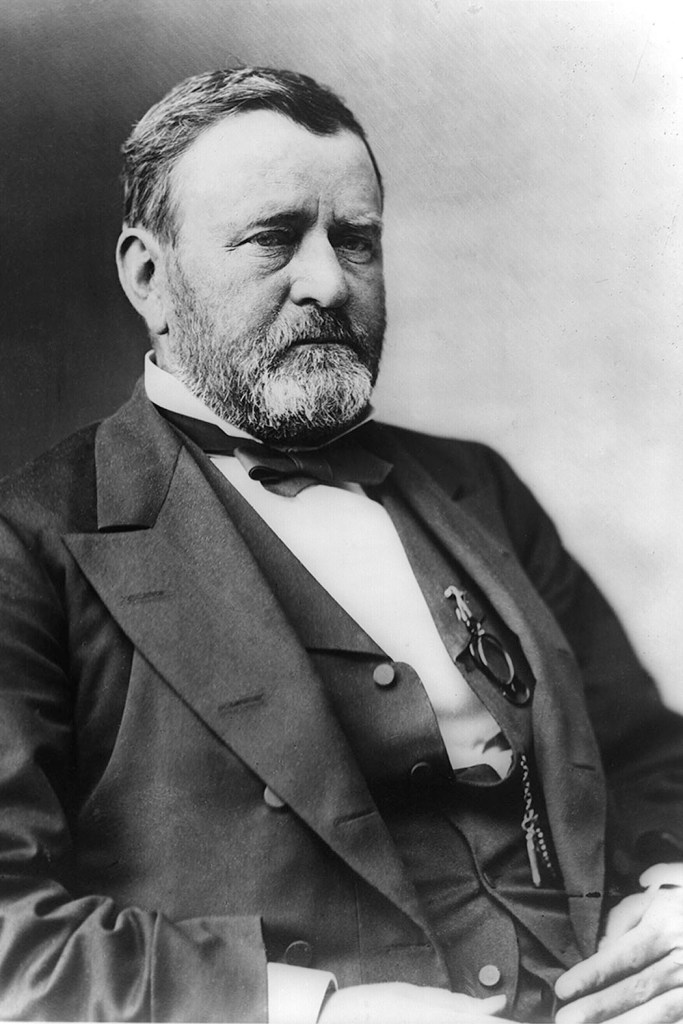

Many of our U.S. presidents were accomplished horsemen. George Washington was known as the “finest horseman of his age;” Thomas Jefferson rode nearly every day until late in life; Andrew Jackson bred and raced horses, stabling several at the White House; and Zachary Taylor grazed his beloved warhorse on the White House lawn. But Ulysses S. Grant is considered by many to be the most skilled horseman to ever occupy the Oval Office.

Even as a small boy, Grant’s connection with horses was obvious. There are numerous stories of young Ulysses breaking in horses nobody else could ride and doing daredevil stunts on horseback. By age five, he was an accomplished and daring rider, known for standing on one leg while maintaining his balance at a gallop. His mother was heard to say, “Horses seem to understand Ulysses.”

Throughout adulthood, Grant continued to ride, train, and care for horses. For him, riding was more than a pastime – it was a form of discipline and excellence. When he attended West Point, his riding abilities were legendary. Fellow cadet James Longstreet described Grant’s skills: “In horsemanship…he was noted as the most proficient in the Academy. In fact, rider and horse held together like the fabled centaur.”

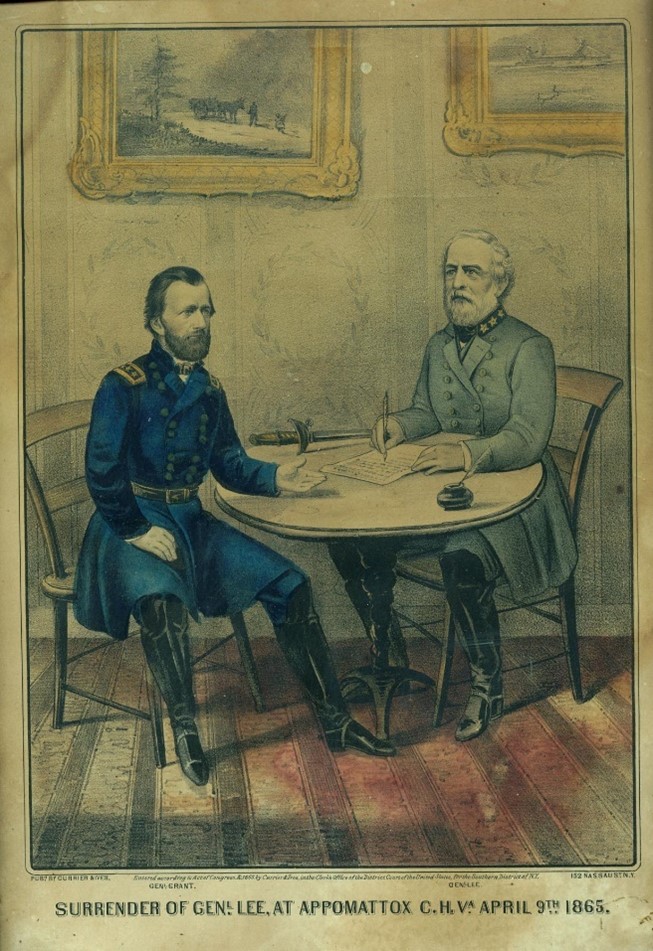

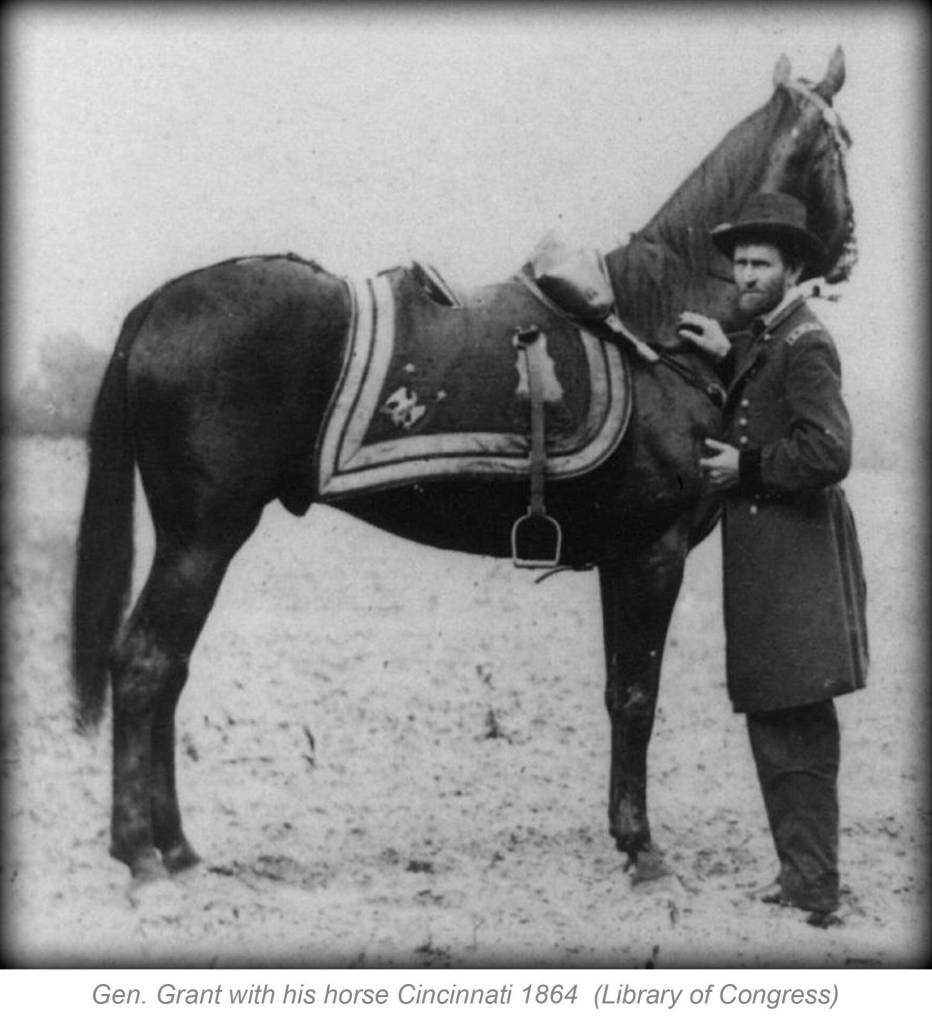

During the Civil War, riding was Grant’s preferred means of transportation since he found it a useful way to scout the terrain. His most famous horse, Cincinnati, was given to him as a gift after the Battle of Chattanooga and quickly became his favorite. (The horse was the son of Lexington, at one time the fastest four-mile thoroughbred in the country.) Cincinnati was a reliable warhorse, remaining even tempered during the fiercest of battles, and Grant continued to own him until the horse’s death of old age.

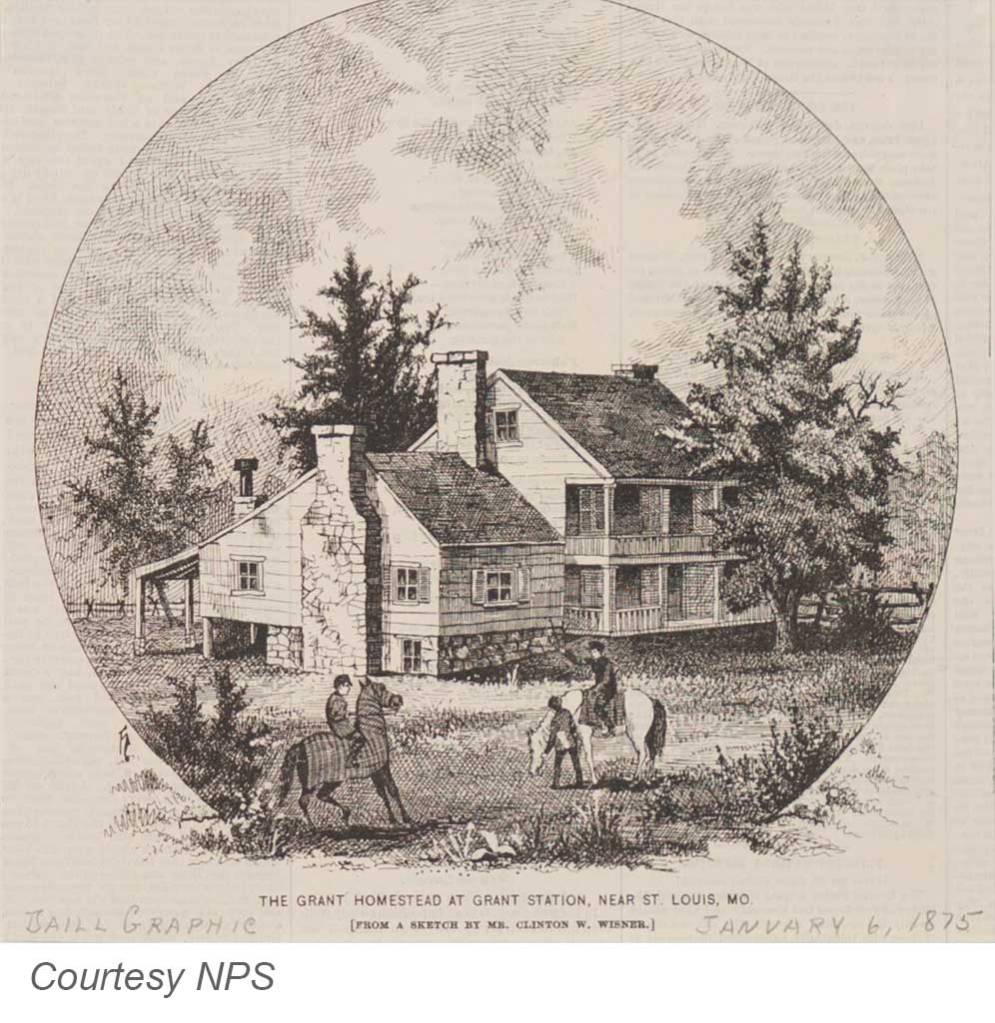

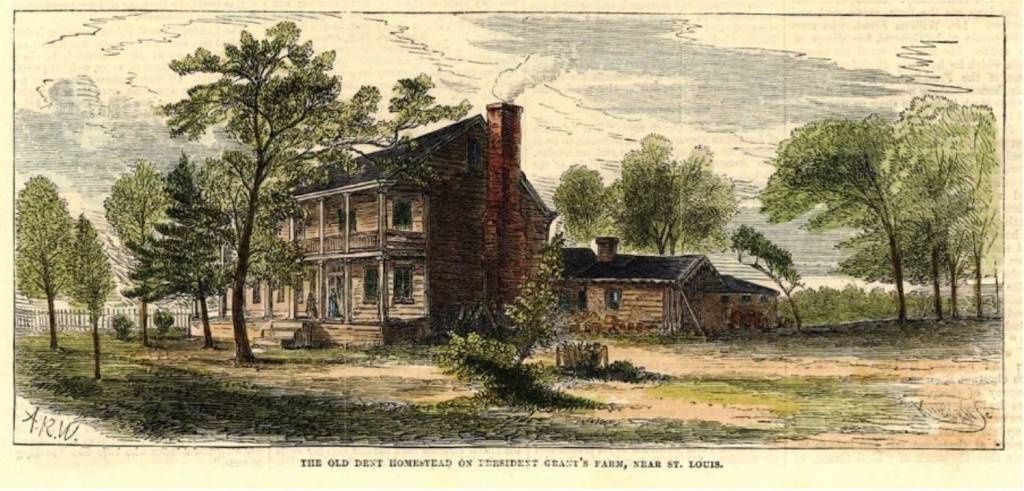

After the war, Grant turned to horse breeding. In 1866 he bought the 860-acre White Haven estate outside St. Louis from his wife’s family, primarily to breed and raise horses. To do this, he needed to convert the bulk of the land from fruits and vegetables to grass and hay to provide feed for the horses. He wrote his caretaker: “I want to get all the ground in grass as soon as it can be got rich enough, except what will be in fruit.”

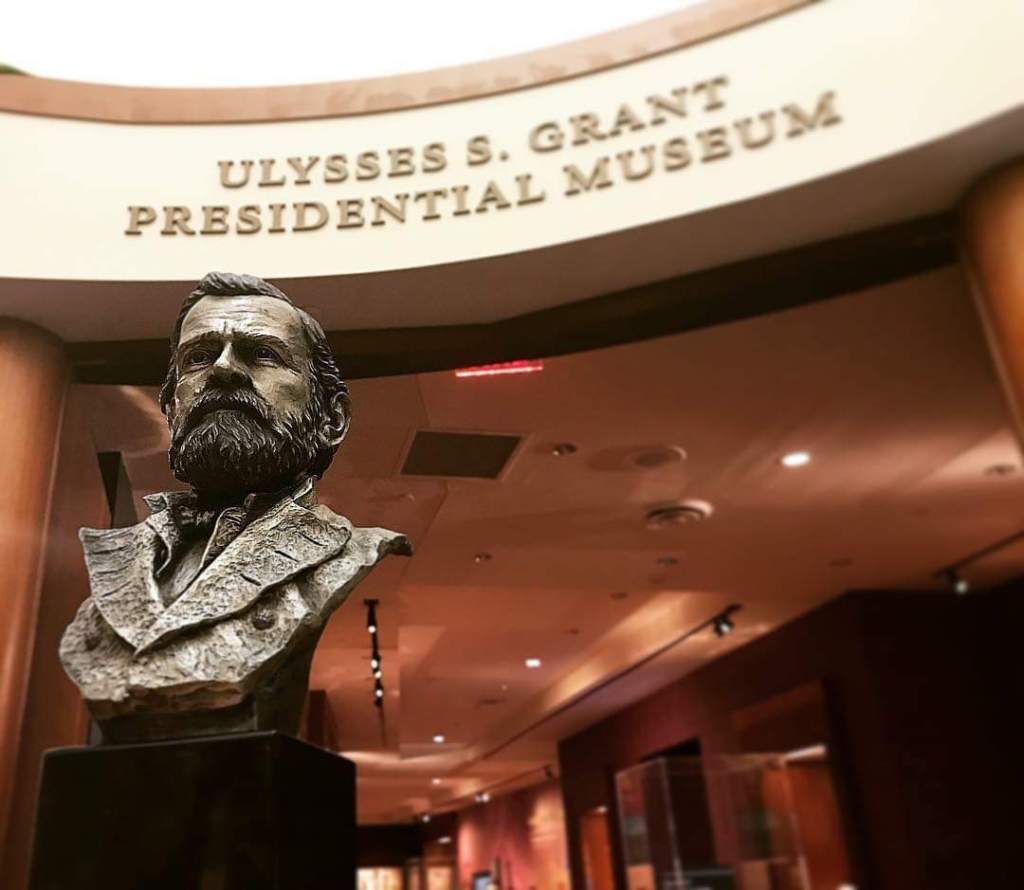

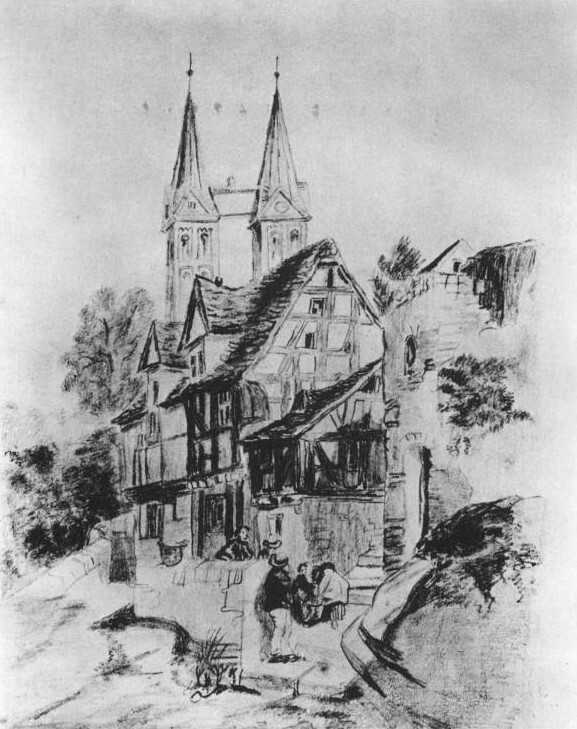

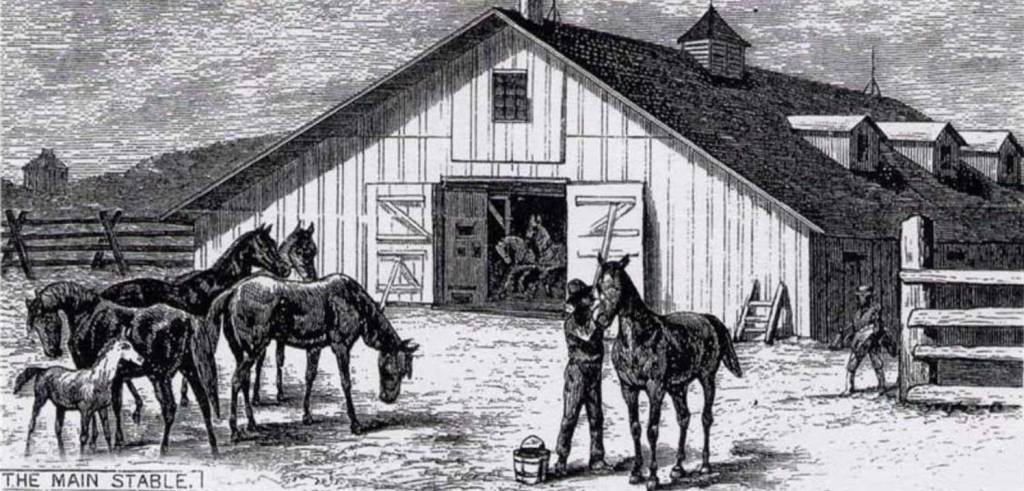

In 1871, he also designed and built a large stable that could accommodate 25 horses, including his beloved trotters, thoroughbreds, and Morgans. Today, the stable remains standing and serves as the museum at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.

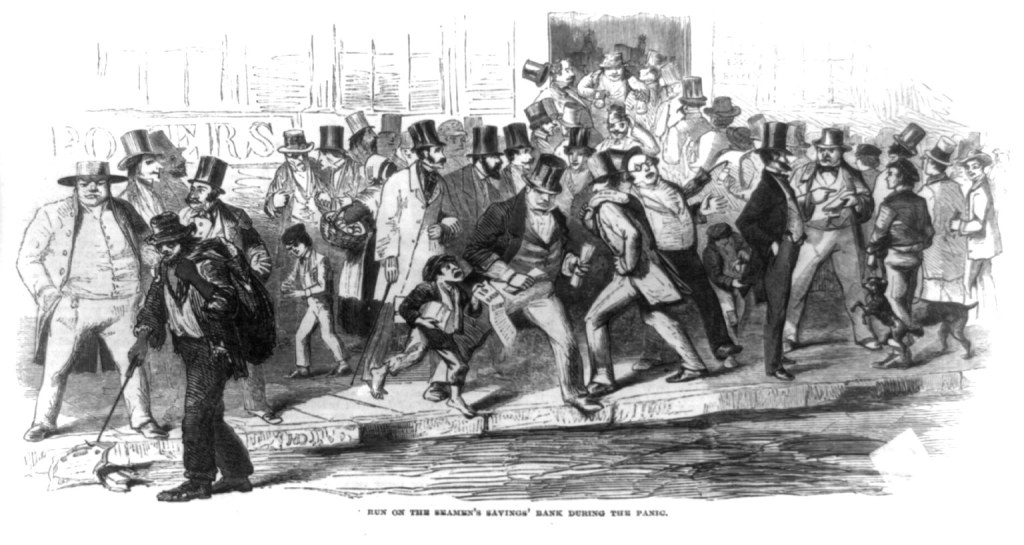

Grant’s breeding farm produced a number of very fine horses, which in 1873 were valued at $25,000 ($675,000 in today’s dollars). And yet the operation was barely turning a profit. Grant decided to shut down the farm and put its resources to auction in 1875. He lost the farm when he was swindled by a New York City business partner in 1884.

Today, the last ten acres of Grant’s horse farm constitute Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site.