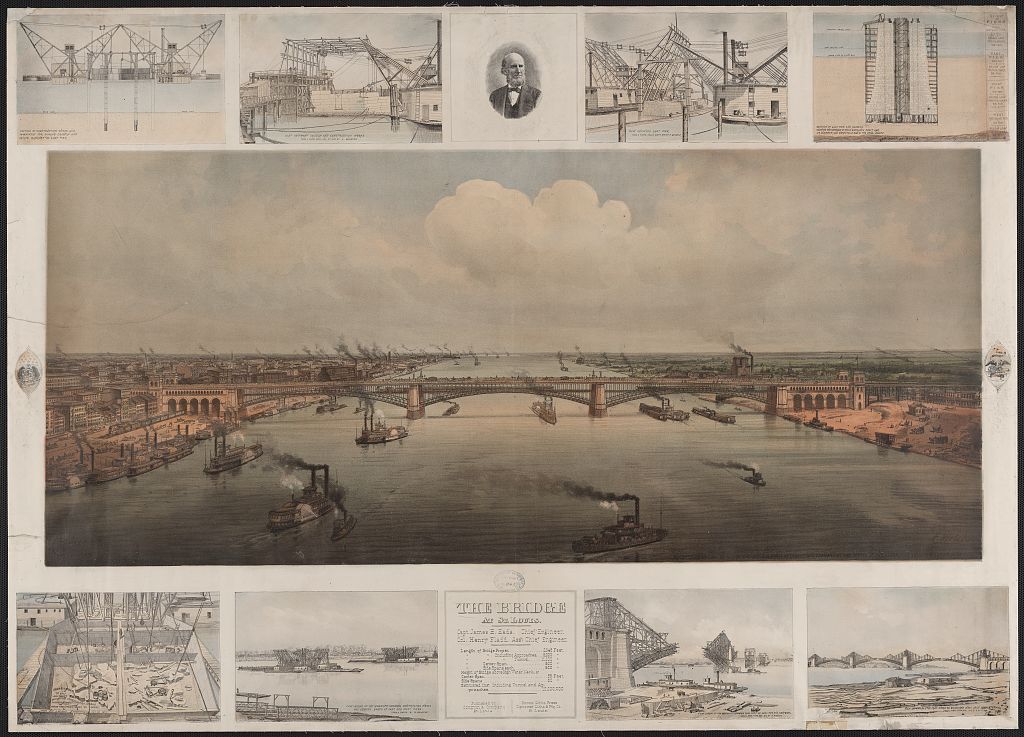

They said it couldn’t be done. They said the design of Eads Bridge was preposterous, that it would snarl riverboat traffic, that riverboats wouldn’t fit under it, that its chief engineer had never designed a bridge, that the Mississippi River’s massive currents and 8-foot-thick ice floes would crush it, that its stone piers wouldn’t support its heavy steel spans.

But against all odds, when the Illinois & St. Louis Bridge (later known as Eads Bridge) was completed in 1874, it became the largest bridge built at the time, and the very first steel bridge. And 150 years later, it still stands as the oldest existing bridge on the Mississippi and a testament to one man’s ingenuity.

In the decade following the Civil War, railroads began to edge out river traffic as the nation’s primary transportation mode. But the Mississippi River was a barrier to rail traffic. Trains would reach the river’s edge, empty their cargo onto a ferry, ship it across the river, then load it onto new trains on the other side. This cumbersome system meant St. Louis was losing out to Chicago as a center of Midwestern commerce.

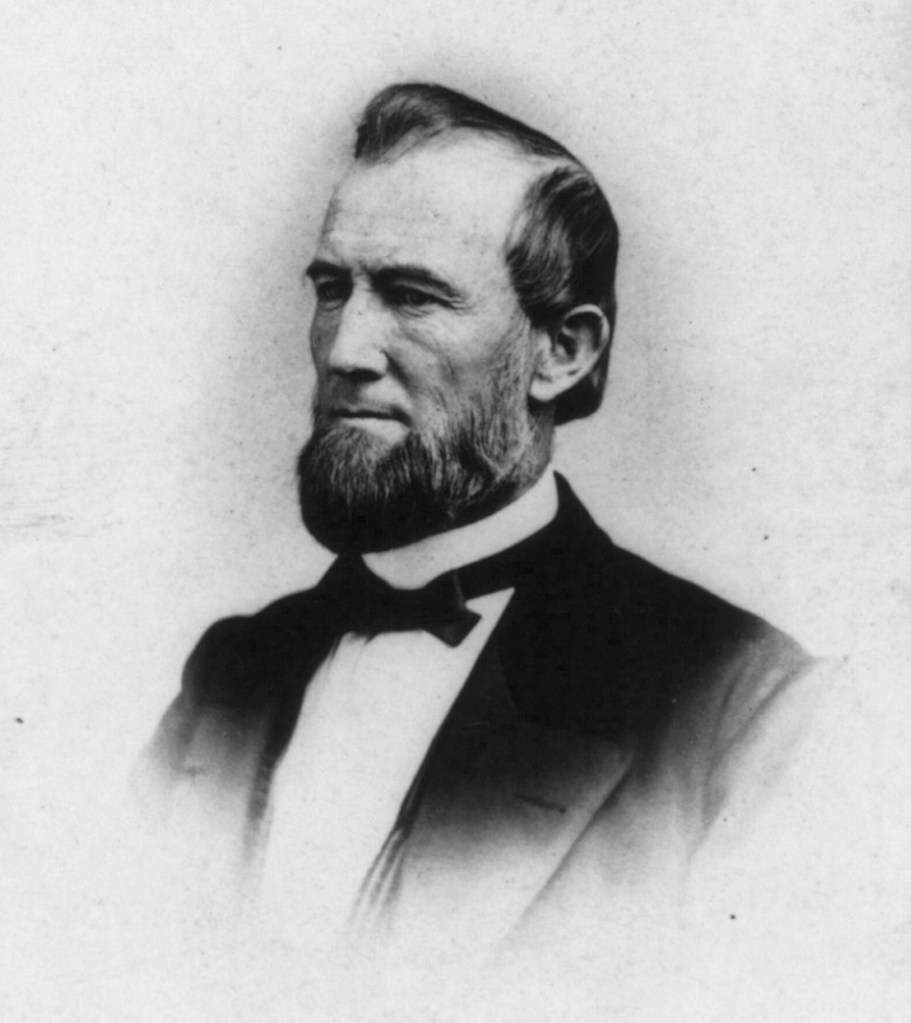

A young self-educated river engineer named James Buchanan Eads offered St. Louis leaders a solution. He had no experience with bridge design, though he’d made a name for himself salvaging wrecks on the river bottom and designing ironclad gunboats for the Union navy during the Civil War.

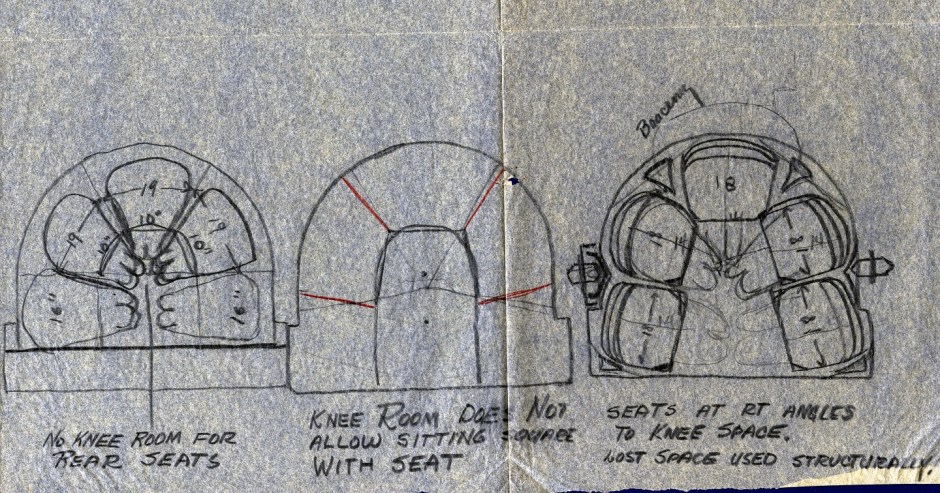

Eads’ design called for giant arches that would support the weight of the bridge from below, leaving ample room for boat traffic while spanning the wide distance from Missouri to Illinois. Naysayers doubted whether the amateur designer’s enormous arches would hold up. Eads’ solution? Steel. The strong and relatively lightweight alloy had never been used as a large-scale building material, but Eads maintained it would be perfect for his bridge.

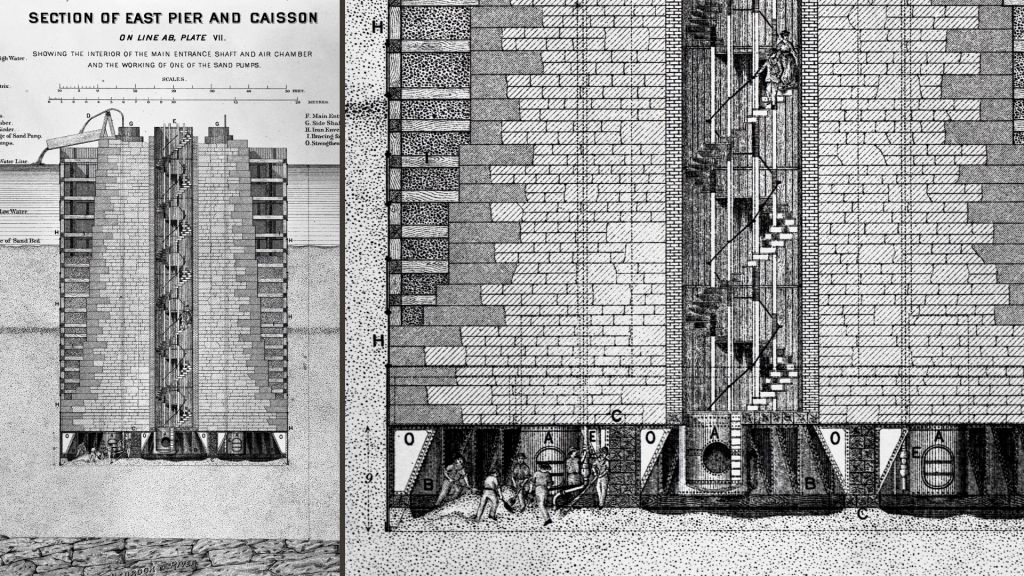

Another equally daunting challenge lay below the water. To ensure the bridge would stand up to the notoriously swift currents of the Mississippi, Eads believed that the four stone piers needed to be anchored not just in mud and silt but in bedrock, more than 100 feet below the water’s surface.

To accomplish such a deep underwater pier construction, he invented a pneumatic caisson, a large watertight chamber filled with compressed air to keep out water and mud. Little did he know, however, that the workers within these pressurized chambers would suffer what came to be known as caisson disease (also known as the bends) when they emerged at the surface too quickly. Despite the establishment of a floating hospital to treat the ailing workmen, at least 15 died as a result.

After seven long years and a cost of more than $7 million, the bridge opened in 1874 – at the time the world’s largest bridge and the first to use structural steel. To reassure those who worried it wouldn’t carry heavy loads, Eads brought in 15 50-ton locomotives filled with coal and water, which safely crossed the bridge in both directions. The grand opening ceremony on July 4th – complete with a 14-mile parade, gun salutes, and a fireworks display – was attended by an estimated 200,000 people on both sides of the river. President Ulysses S. Grant was in attendance, as were a host of other elected officials and dignitaries.

The National Park Service designated Eads Bridge a National Historic Landmark in 1964, and it has since received accolades from the city of St. Louis and from numerous professional organizations. It continues to carry automobile and light rail traffic across the Mississippi River today, just north of the Gateway Arch.

Eads Bridge fans will want to attend one of Gateway Arch National Park’s upcoming educational programs about the bridge offered by historian Paul Giroux and park rangers inside the park visitor center. The Arch museum will also feature artifacts from the original bridge. And The Arch Store has a number of commemorative Eads Bridge products and books available for purchase, including the newly published Spanning the Gilded Age.