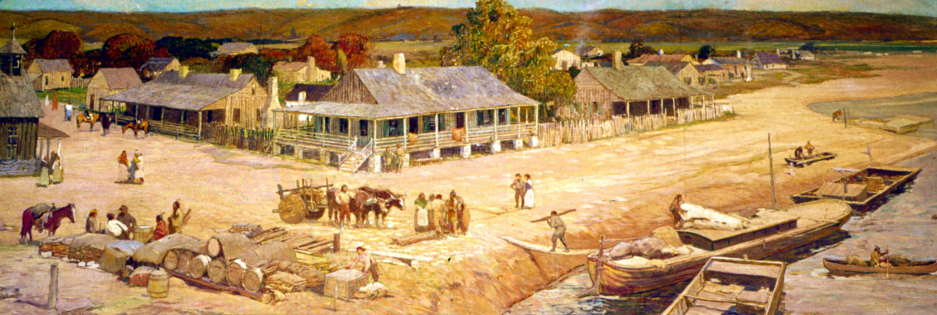

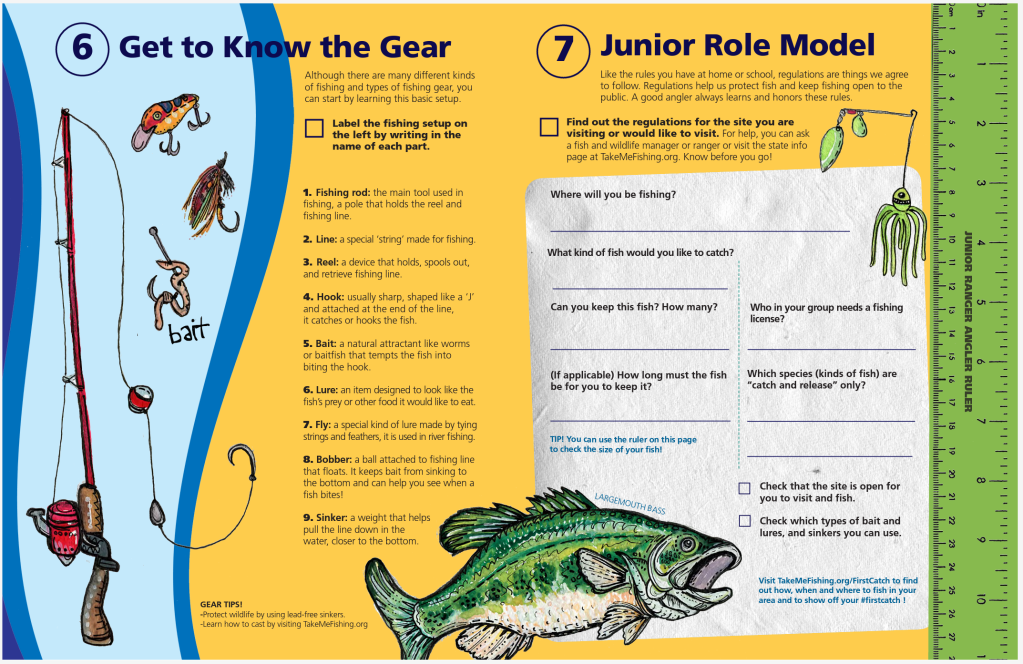

How do YOU celebrate the holidays? Your answer may depend upon your religious practices or your family traditions. But if you’d lived in the French colonial village of Ste. Geneviève in the 1700s, chances are you and your neighbors would have commemorated the winter holidays in very similar ways.

The townspeople of 18th-century Ste. Geneviève were predominantly Catholic, having brought their religious and cultural traditions from France. One of their most festive seasons of the year was December to mid-January. The four weeks prior to Christmas was Advent, a time of reflection, fasting, and merriment. The culmination of Advent was Christmas Eve, when most of the community attended midnight Mass.

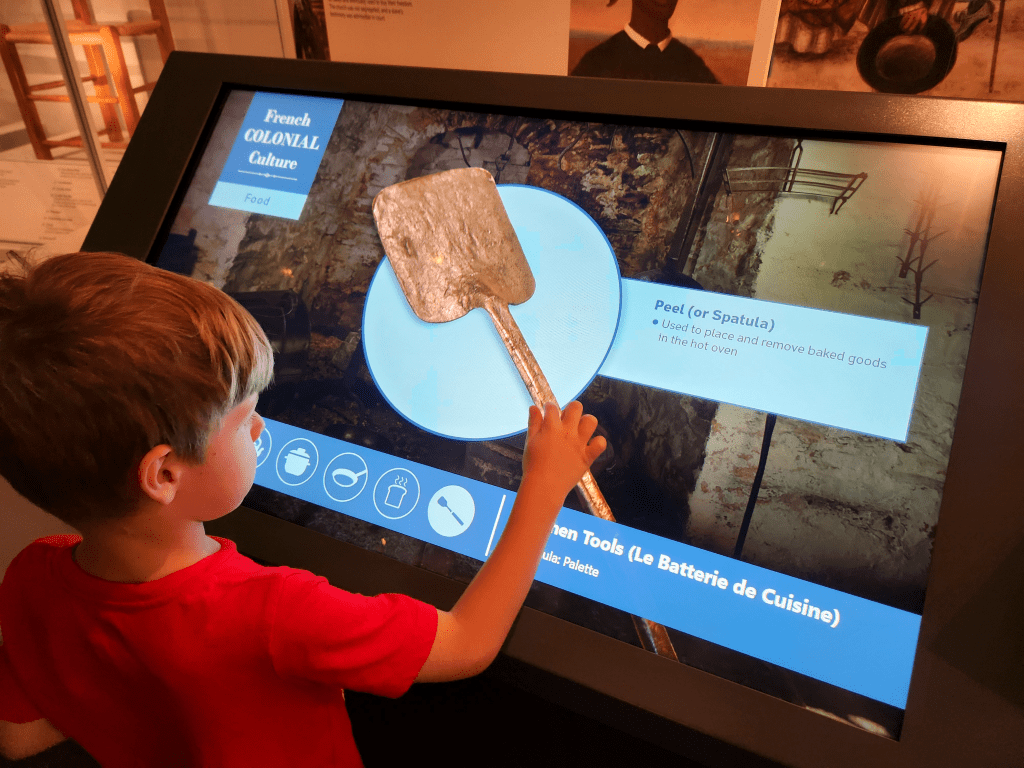

After the church service ended, the townsfolk gathered with their extended families for a feast called La Réveillon. This special breakfast would start in the early hours of the morning and proceed well into the next day. La Réveillon featured traditional breakfast foods such as eggs, sausage, and breads along with non-traditional items like puddings, stews, and cakes. Christmas Day festivities would continue throughout the day with more feasting, church services, and in some households, balls or parties.

During this time of year the Frenchwomen of Ste. Geneviève were able to show off their cooking skills, using the new foods they found available in the New World, and incorporating African and Native American influences.

In 1811 Henry M. Brackenridge wrote that “The table was provided in a very different manner from that of the generality of Americans. With the poorest French peasant, cookery is an art well understood. They make great use of vegetables and prepared in a manner to be wholesome and palatable. Instead of roast and fried, they had soups and fricassees, and gumbos…”

from 1820. Library of Congress)

The next holiday celebration, La Guiannée, took place on New Year’s Eve. On the evening of December 31st, a troupe of male singers dressed in costume went door-to-door throughout the community. As they sang, they asked for donations from each household for the upcoming Epiphany feast. The group collected things like lard, poultry, eggs, wheat, and candles to feed the community and decorate for the Epiphany Celebration. (The 250-year-old tradition of La Guiannée is still celebrated in Ste. Geneviève to this day.)

As the years went on and the village changed, the holiday traditions for the French Catholic residents of Ste. Geneviève ebbed and flowed. With the arrival of new residents from American and German backgrounds, new traditions emerged, and old traditions adapted to suit the growing community. The changes have allowed for many of the French Catholic traditions to continue into the present-day community.

If you haven’t yet visited the town, or our park partner Ste. Geneviève National Historical Park, winter can be a great time to stop by. Be sure to check the park’s website for upcoming activities before you go.