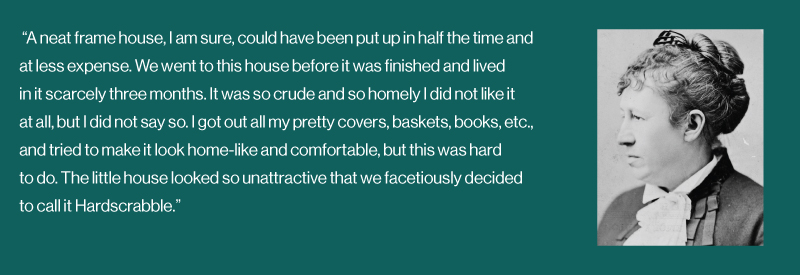

Who doesn’t love a birthday? Well, Julia Dent Grant has a milestone birthday this month. America’s 18th First Lady was born 200 years ago – on January 26, 1826. Throughout this year Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site will celebrate this auspicious event with special programs and exhibits that focus on various aspects of her life.

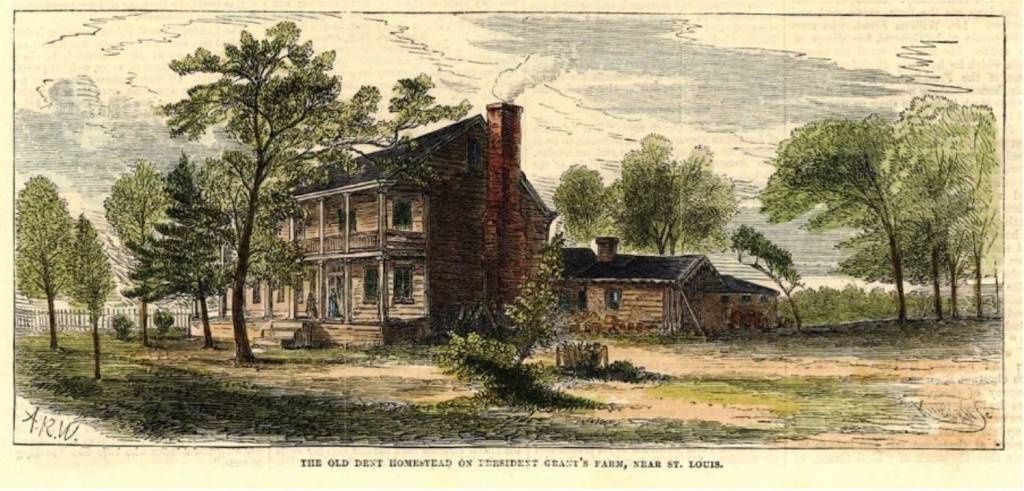

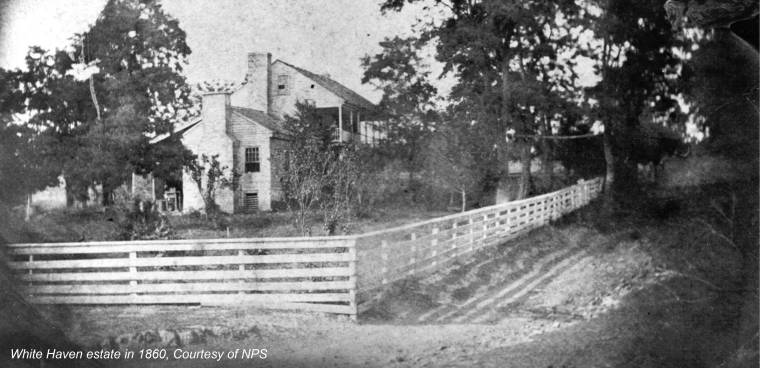

The fifth of seven children, Julia Boggs Dent was born in St. Louis and raised in comfortable surroundings on the 850-acre White Haven plantation. She was an active child who fished, played piano, rode horses, and played in the woods. Many of her early playmates were children of the enslaved who lived on the property. Some of these children would later become her servants.

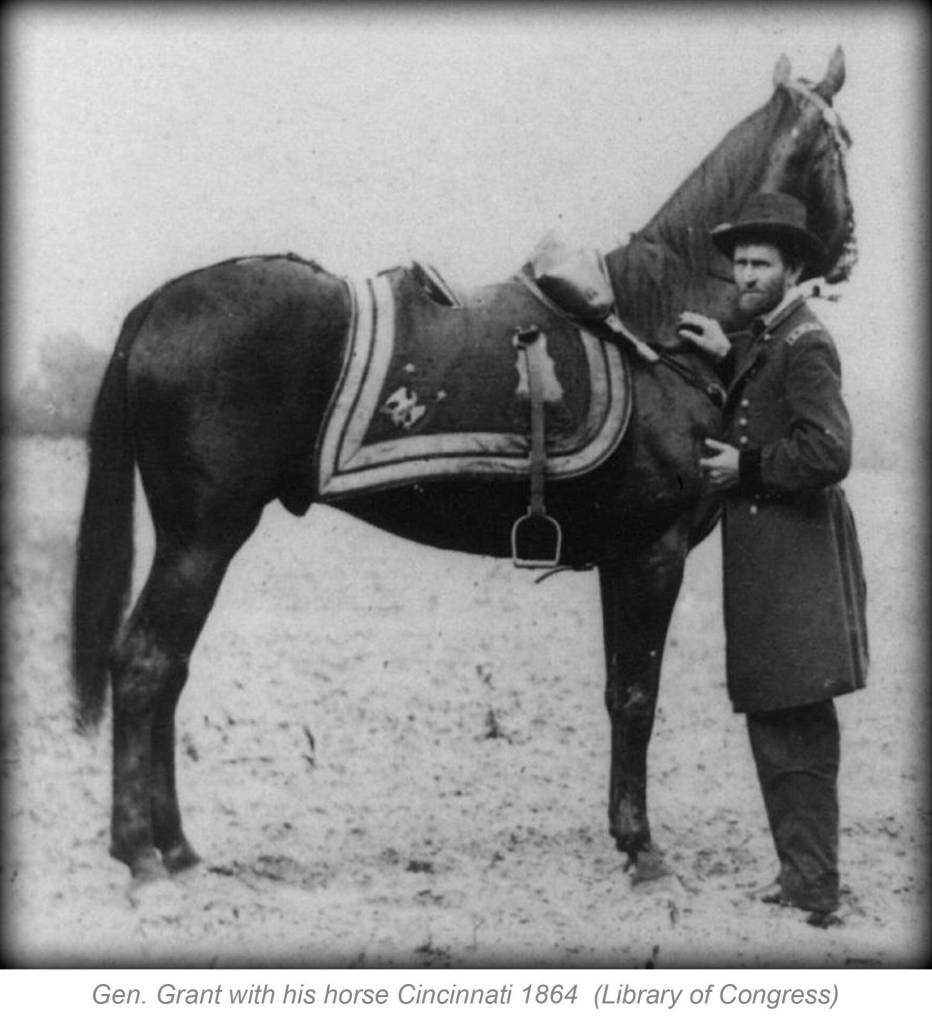

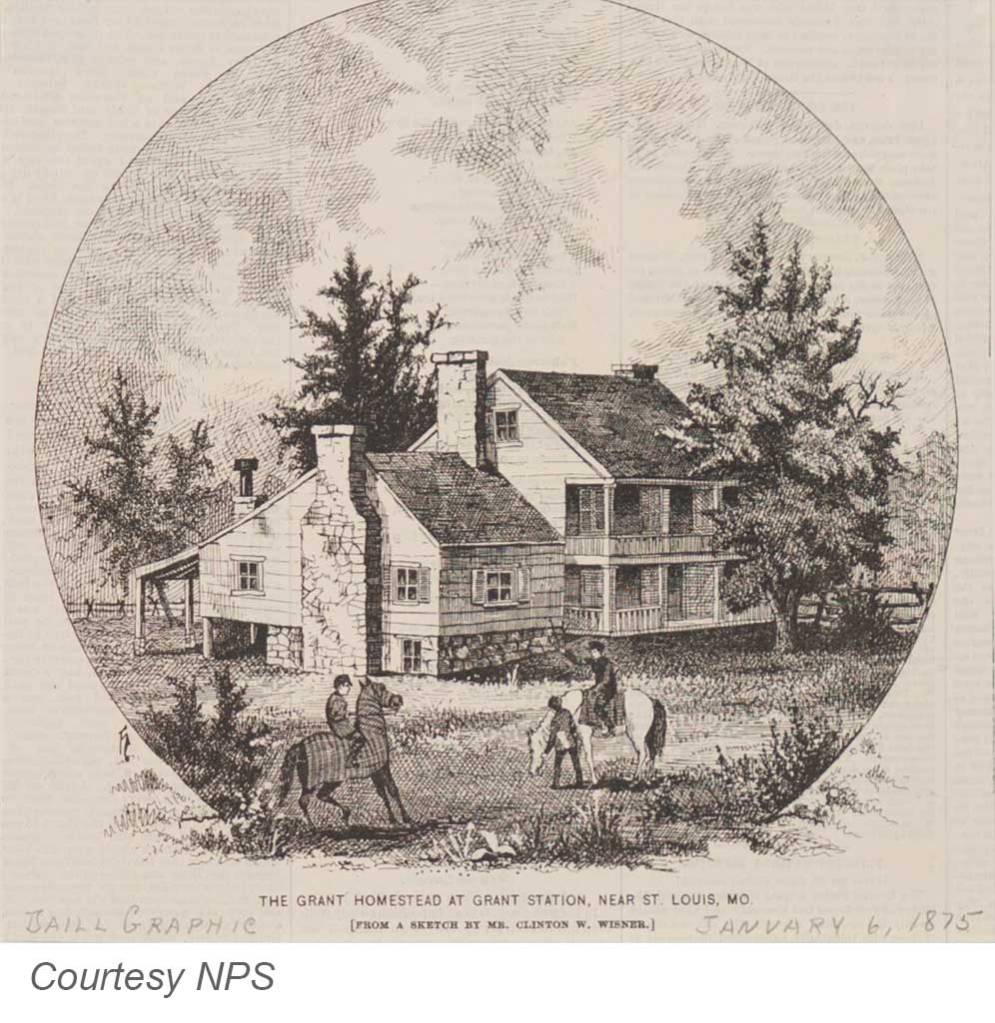

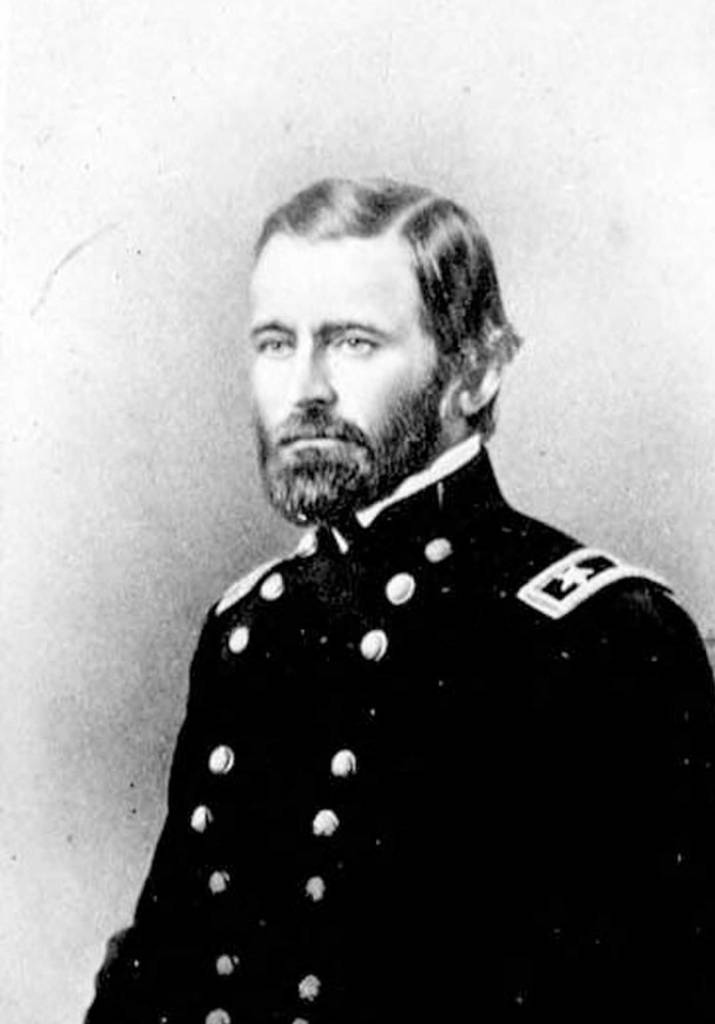

As a schoolgirl, Julia declared that she would marry “a soldier, a gallant, brave, dashing soldier.” After returning home from boarding school, she met that soldier in Lt. Ulysses S. Grant, a former West Point roommate of Julia’s brother Frederick. When he was stationed at nearby Jefferson Barracks, Ulysses soon became a frequent visitor to White Haven, where he and Julia enjoyed walks and horseback rides. The couple fell in love quickly, and Grant proposed marriage on the front porch of White Haven in the spring of 1844. Because of his military service, however, they had to wait until 1848 to marry.

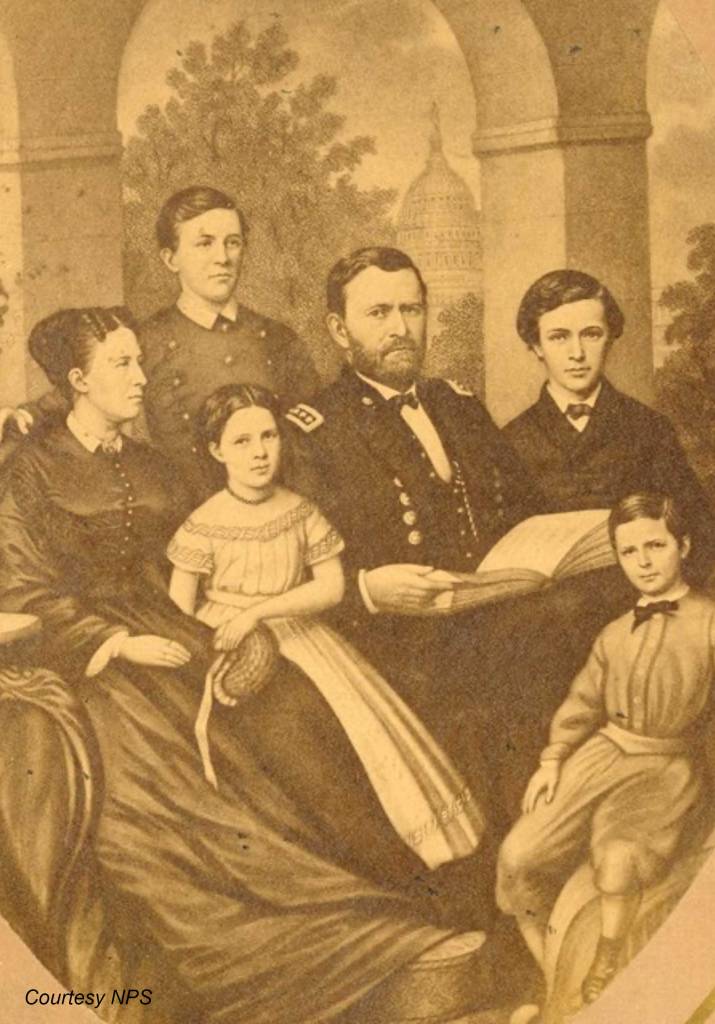

Neither set of parents was enthusiastic about the match – Julia’s were worried about Grant’s earning potential, while his parents objected to the Dents’ ownership of enslaved workers. However, the couple seemed deeply attached to one another and remained so throughout their 37-year marriage. Their four children were born between 1850 and 1858.

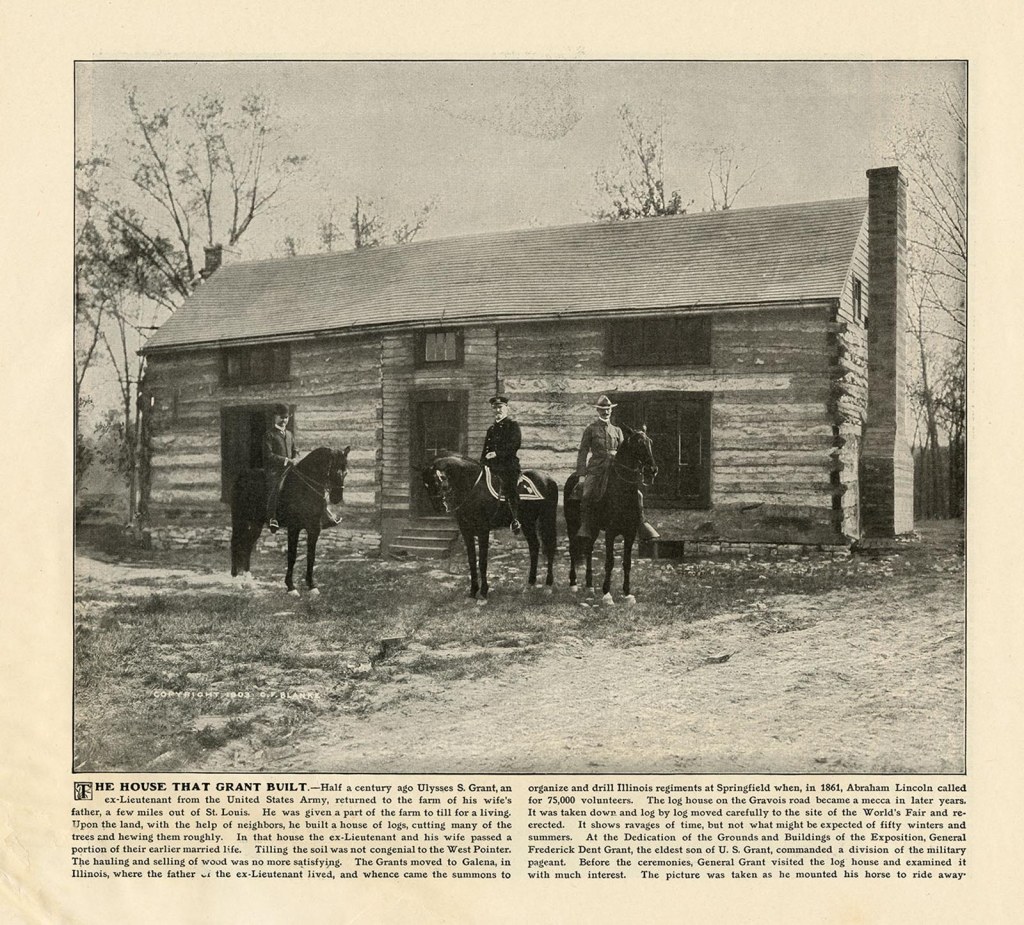

When Ulysses’ military career took him to remote locations, Julia did not accompany him. He suffered from loneliness and eventually resigned from the Army, returning to White Haven in 1854 to try his hand at farming. Julia considered herself “a splendid farmer’s wife,” raising chickens and even churning butter, though most of the daily chores were left to the enslaved laborers.

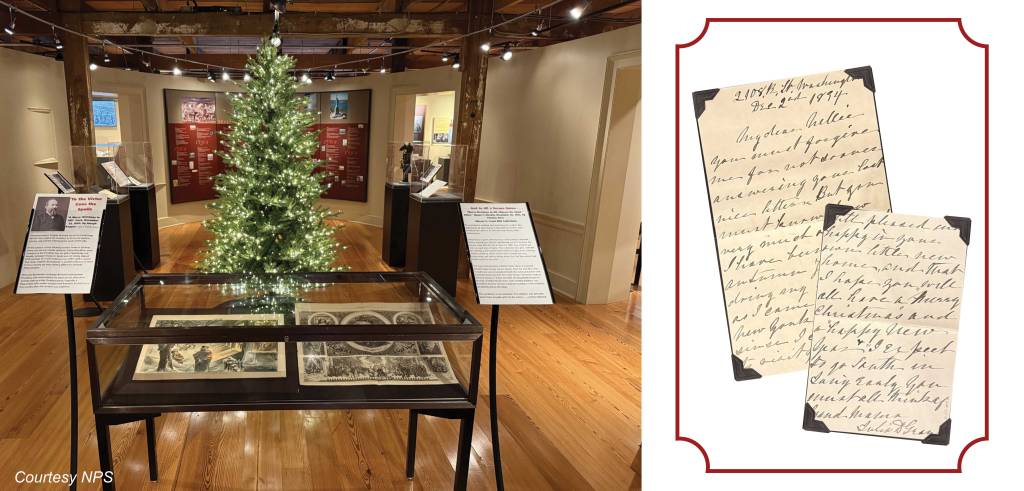

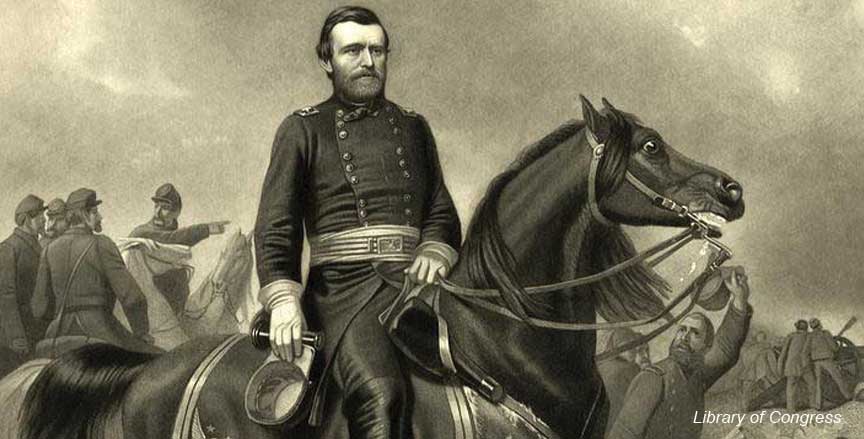

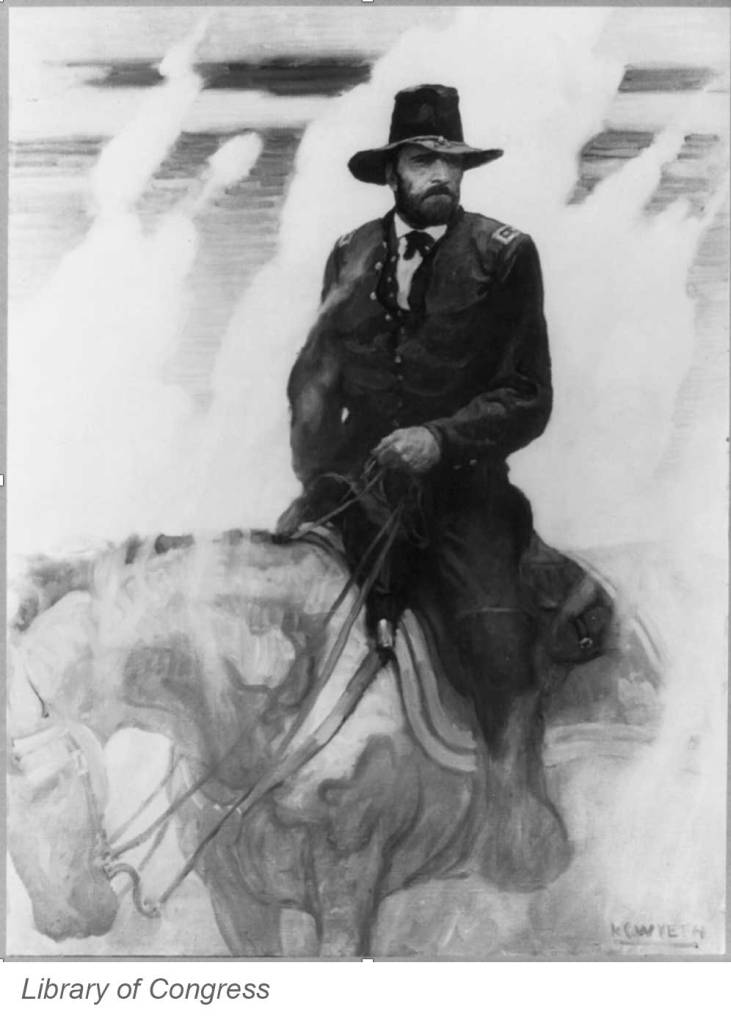

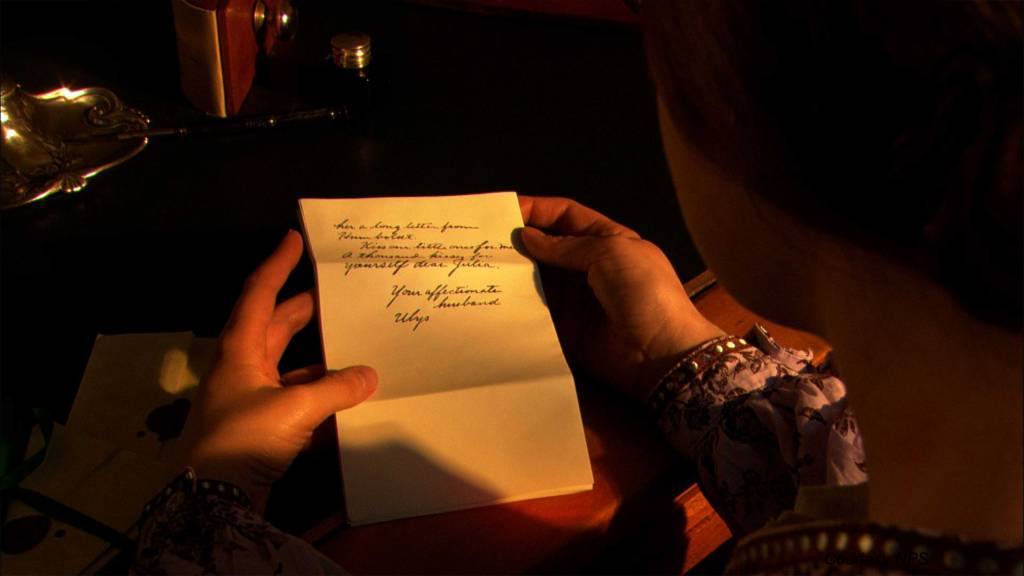

The Civil War dramatically altered the Grants’ lives. In 1861 Ulysses left to serve in the Union army, and his responsibilities kept him away from home for most of the war. Letters helped ease the pain of separation, and Julia frequently traveled to her husband’s encampments, both alone and with the children. For a close-up look at the couple’s intimate relationship, check out A Thousand Kisses, a short video that JNPA produced on behalf of the historic site.

When Grant was elected President in 1869, Julia became a trusted confidant to her husband and often participated in presidential matters. She attended Senate hearings, read through Grant’s mail, and met with cabinet members, senators, justices, and diplomats. She apparently enjoyed her role as hostess to the nation and brought a home-like atmosphere to the White House.

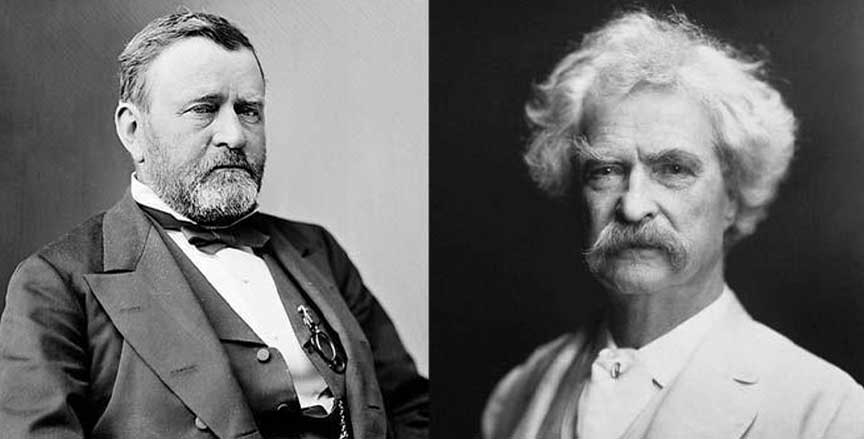

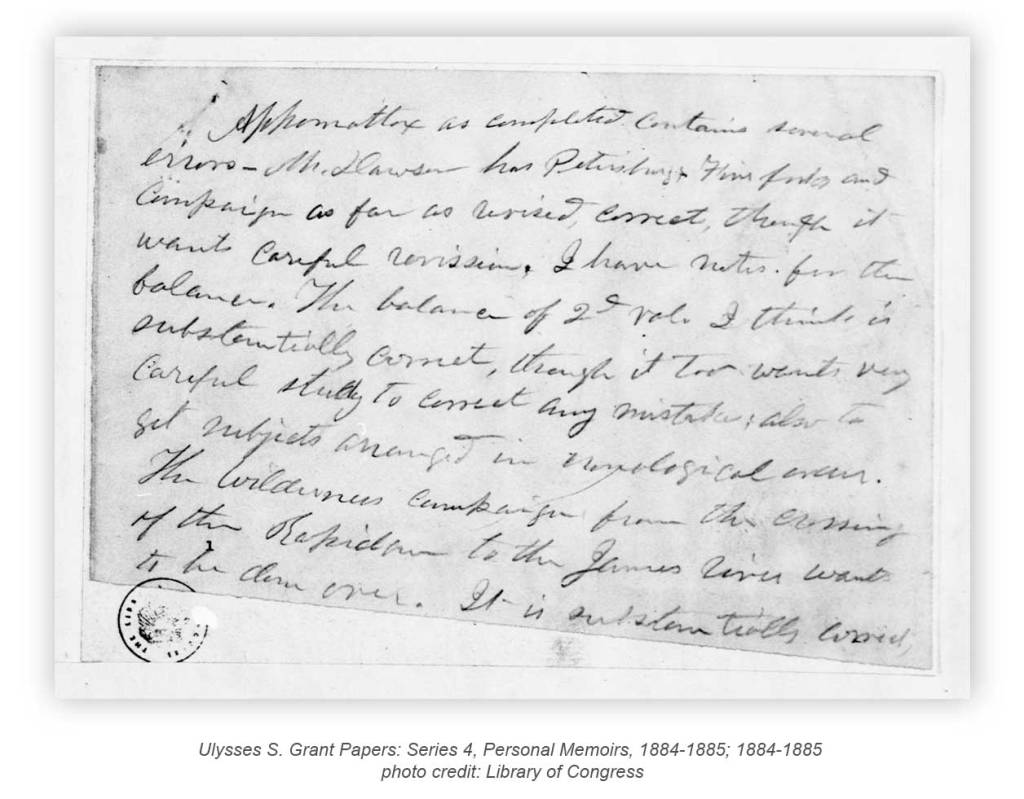

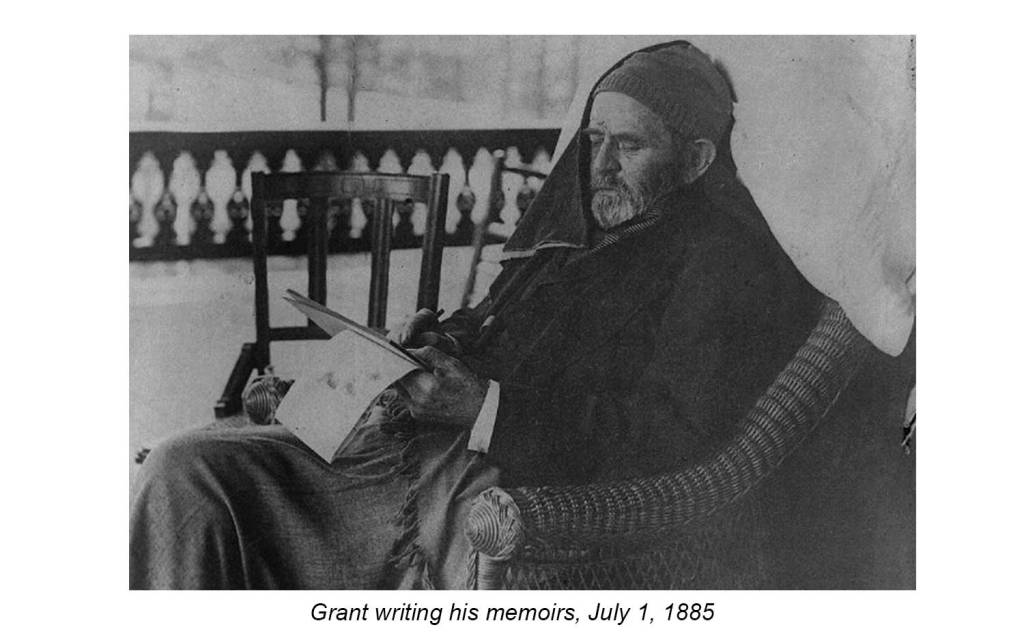

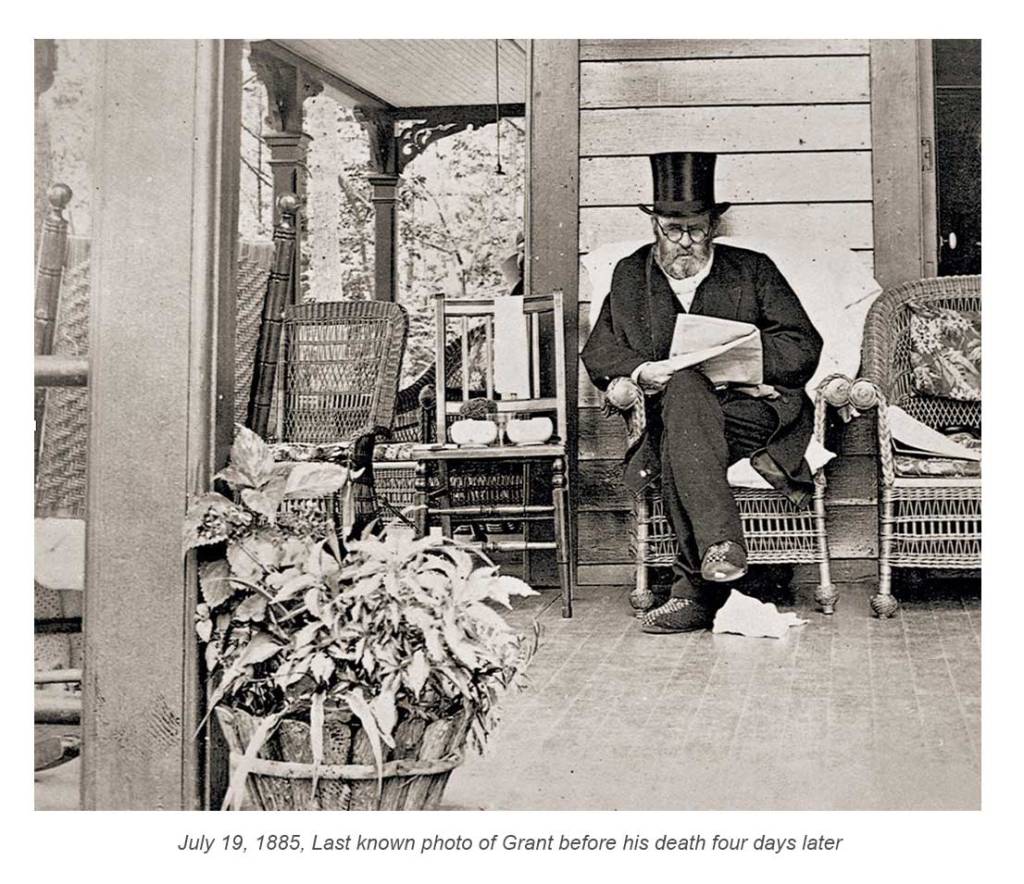

Grant succumbed to throat cancer in 1885, but the profits from publication of his memoirs left Julia a wealthy woman. (Pick up your copy of his memoirs at the park or from our online store.) For the next 17 years, she worked to sustain the memory of her beloved husband. She died in 1902.

Those interested in learning more about Julia are invited to attend Julia Dent Grant – Diplomat, a special lecture at Ulysses S. Grant National Historic Site on Saturday January 24. The presentation will trace Julia‘s life from her childhood when she interceded with her father on behalf of the White Haven enslaved to her widowhood when she befriended Varina Davis, wife of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. It will also focus on Julia Dent Grant’s role as a diplomat and unofficial ambassador. The program is free but call 314-842-1867 ext. 230 for reservations.